The race for sustainable aviation fuel

Air travel needs new fuels to go green.

The race to make them is heating up

Sir Frank Whittle’s invention of the jet engine paved the way for aircraft to fly faster, higher and for longer. However, as they streak through the air they burn through an enormous amount of fossil fuel, which releases an enormous amount of carbon into our atmosphere.

As BP states, a return flight between London and San Francisco has a carbon footprint per economy ticket of nearly 1 tonne of CO2e. Put another way, The Guardian reveals that a single long-haul flight can generate more carbon emissions than the average person in 56 different countries will generate in an entire year.

While the Covid pandemic just about ground air travel to a halt in 2020, flights have been ramping up since. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), aviation emissions rose in 2022 to reach nearly 80% of the pre-pandemic levels, and by 2025 these levels will be exceeded. Currently commercial airlines require in excess of 360 billion litres of aviation fuel a year.

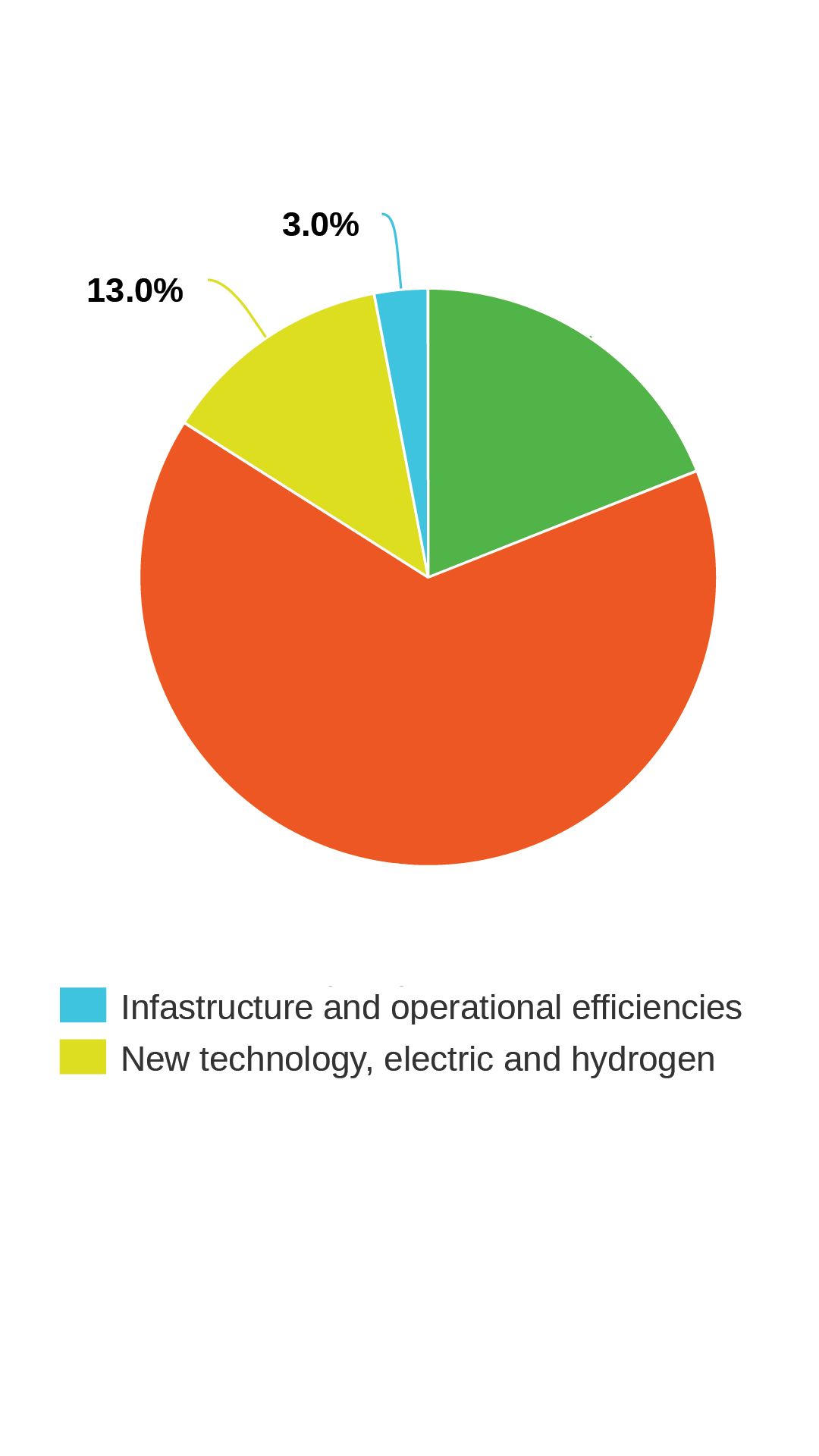

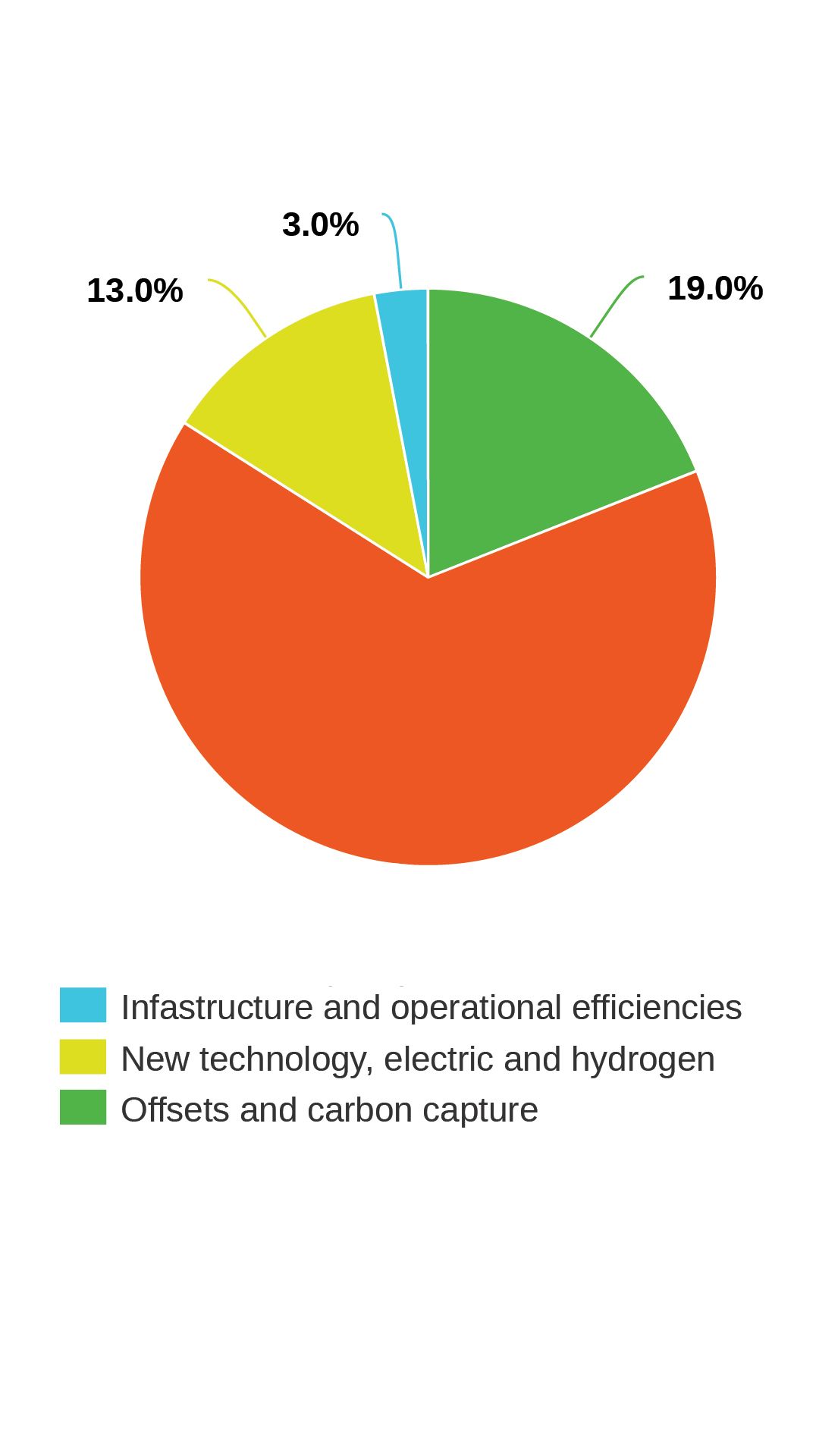

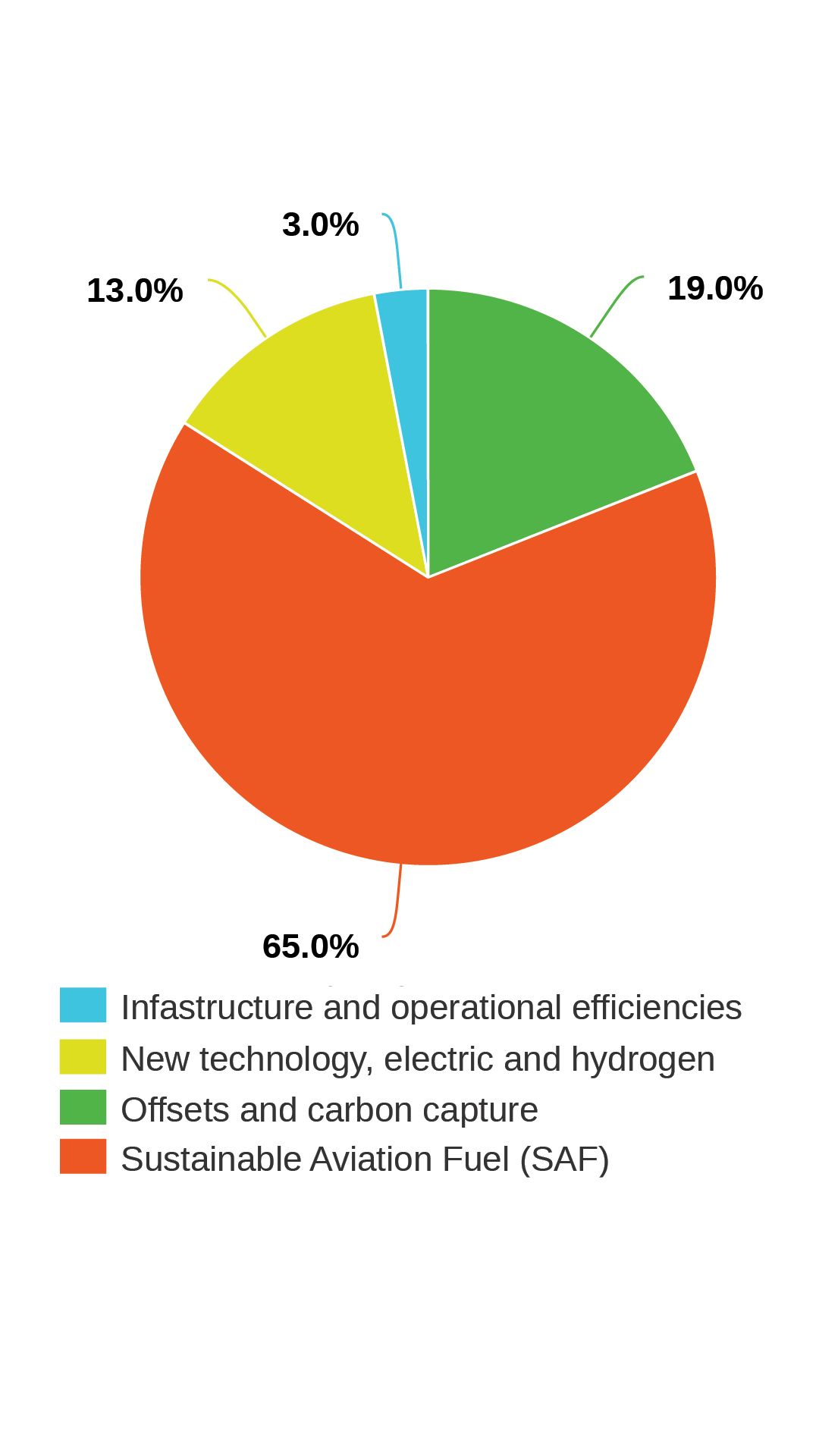

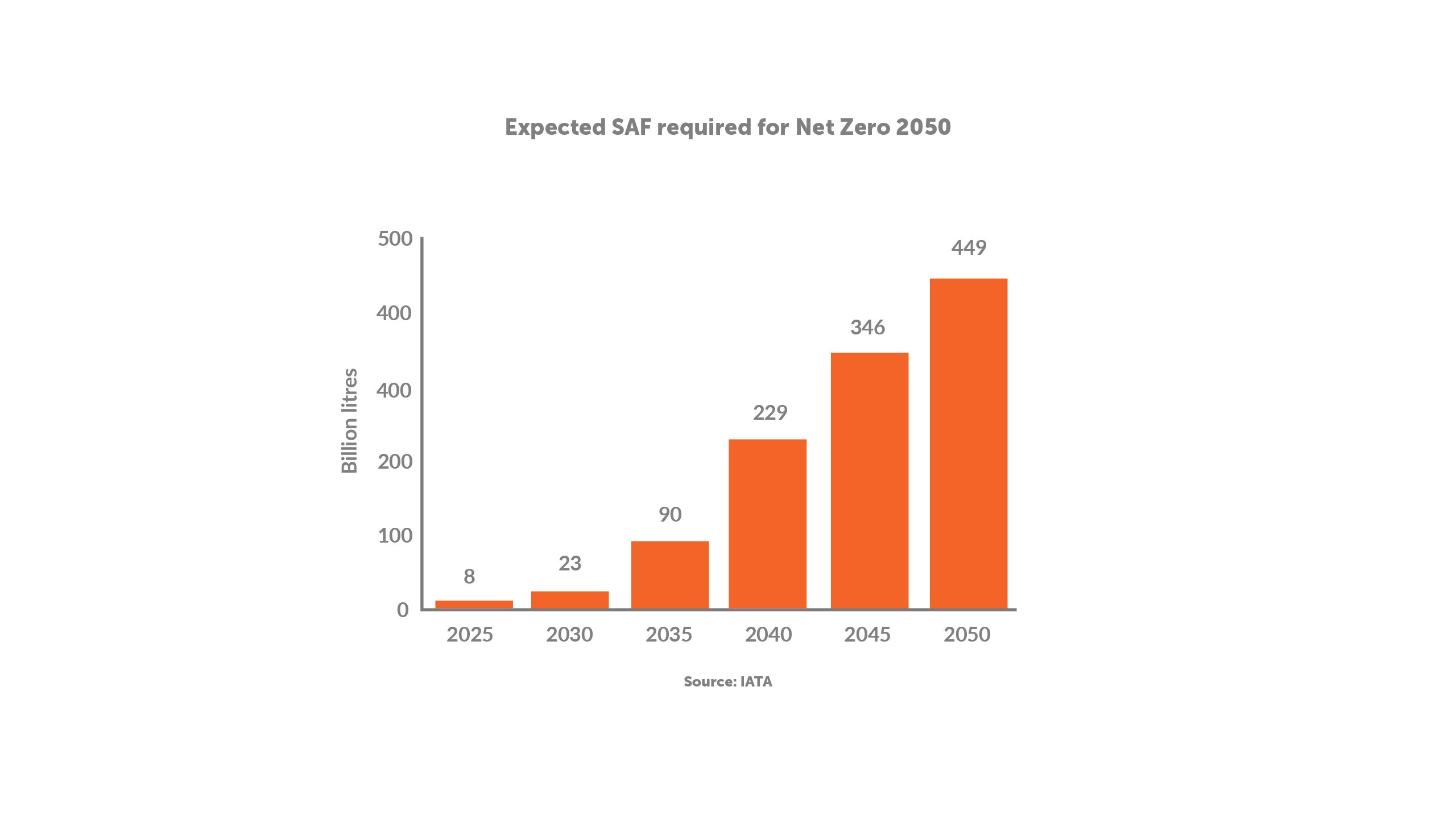

To reduce the amount of carbon from this vast quantity of fuel, the industry is focusing on sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) as the most expedient and scaleable means of decarbonisation in the short and medium term. IATA estimates that the use of SAF could contribute 65% of the reduction in emissions needed by aviation to reach net zero in 2050.

SAF is sustainable in that it is produced by recycling already existing sources or feedstocks. While it still produces carbon when burned in flight, it reduces carbon emissions over the lifecycle of the fuel. IATA estimates that SAF has the potential to reduce carbon in aviation by up to 80%

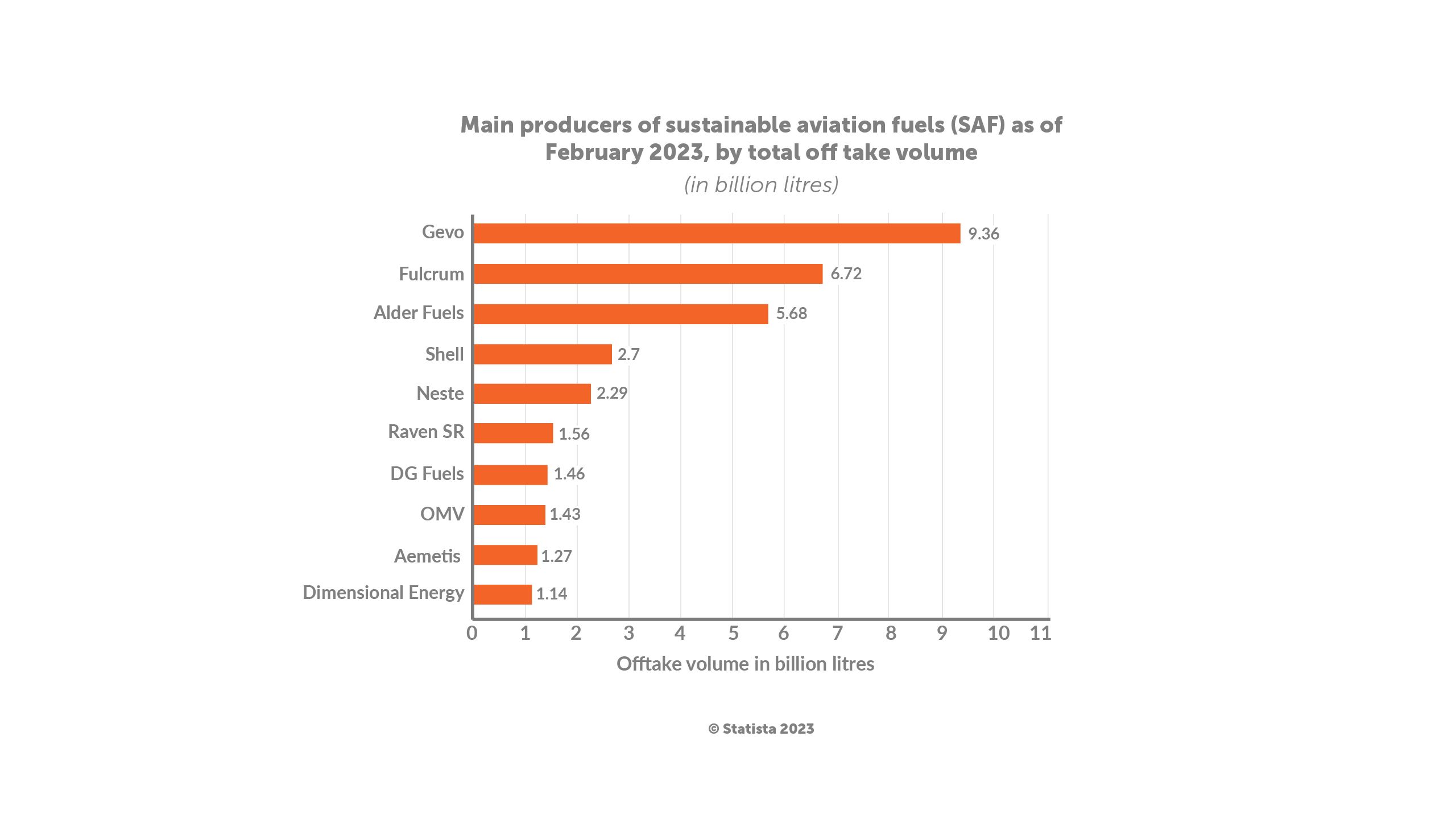

The main way of producing SAF currently is through a process known as hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA). This process uses a variety of feedstocks including waste oils from animals or plants, solid municipal waste, and forestry and agricultural residues. Leading the pack of main SAF producers is US-based Gevo, which uses sustainably grown industrial corn as a feedstock in its alcohol-to-jet process.

Power-to-liquid (PtL) fuel is a synthetic SAF that offers a promising alternative to HEFA-based SAF as it is produced only from renewable electricity, water and captured CO2. It is still in the fledgling stages but, as McKinsey reports, PtL is an important part of the SAF mix and producers need to come online to meet the demand for PtL, which is estimated to be in the range of 140 to 280 tonnes in 2050.

Supply of SAF is currently small

The advantage of SAF is that it can be used as a ‘drop-in’ fuel in current aircraft and airport infrastructure with no major adjustments to fuel delivery equipment. It is not used ‘neat’ as current legislation requires a maximum 50% blend with traditional jet fuel.

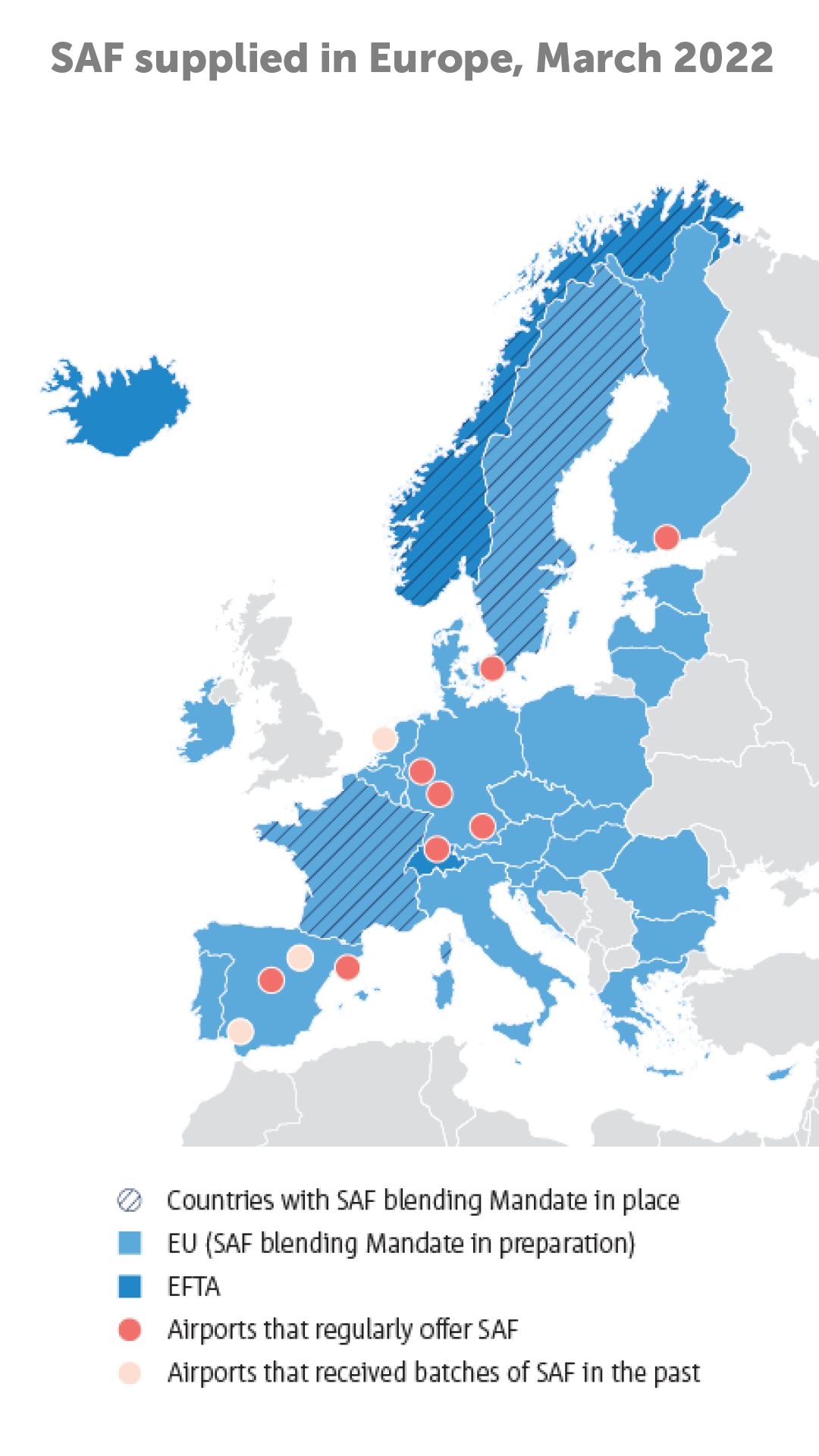

Globally only 14 airports supply SAF. For instance, at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, SAF is available on request through a partnership with Neste, a Helsinki-headquartered global supplier of renewable fuels.

With the clock ticking on decarbonisation targets, the demand for SAF is very high. For instance, Virgin Atlantic has stated that, as soon as SAF becomes readily available, the airline is all set to use it and is fully committed to SAF forming 10% of its fuel consumption by 2030, in line with IATA’s targets.

The issue is that the supply of SAF is still very low. In the EU, SAF accounted for less than 0.05%t of total jet fuel demand in 2020.

A single long-haul flight can generate more carbon emissions than the average person in 56 different countries will generate in an entire year

While supply is increasing – IATA reported that in 2022 production of SAF soared over 200% to at least 300 million litres – this is just a drop in the fuel tank of what’s needed to meet targets. IATA projects that 23 billion litres of SAF will be needed globally by 2030, climbing rapidly to 450 billion litres in 2050.

Leading the SAF pack

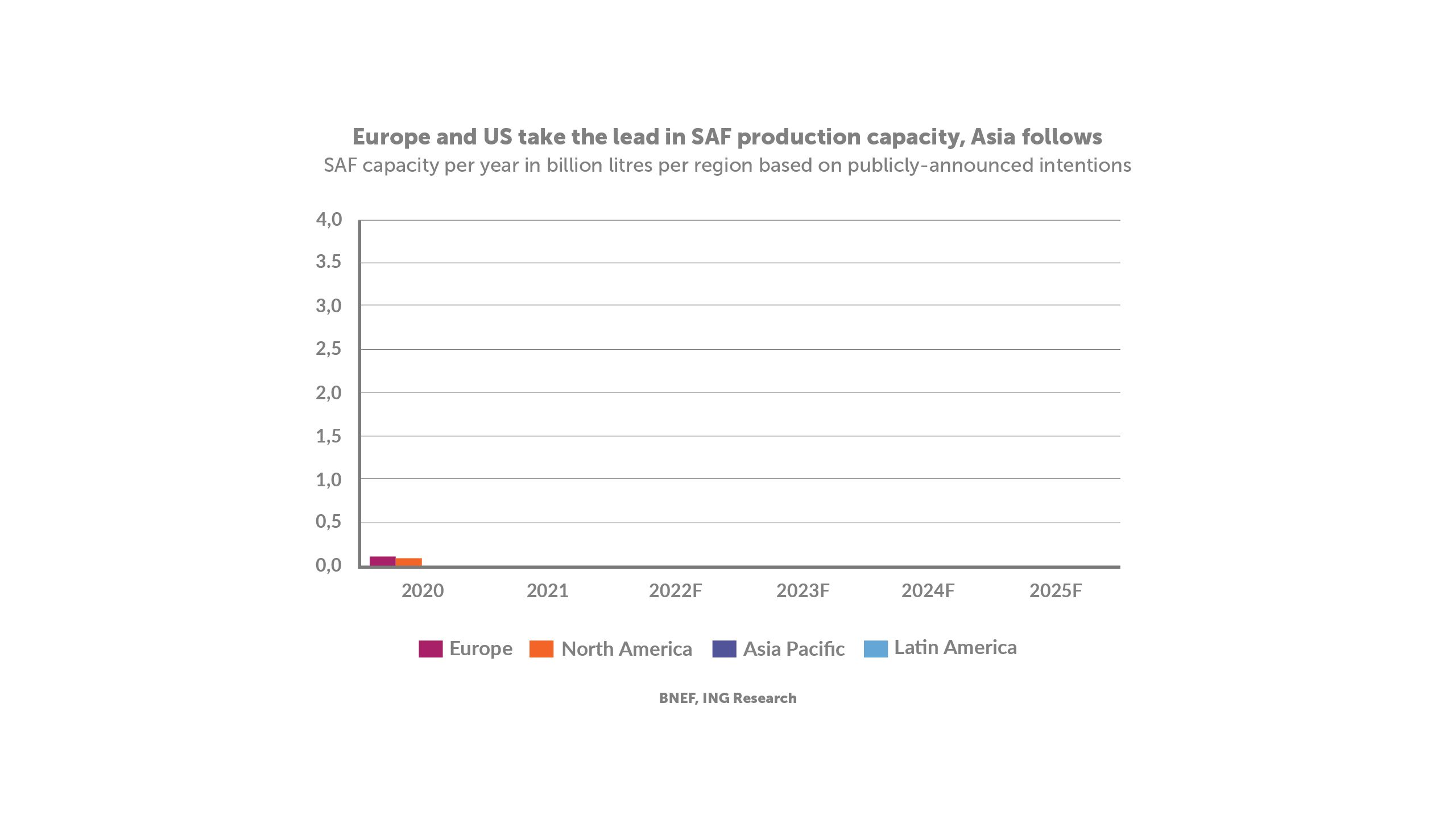

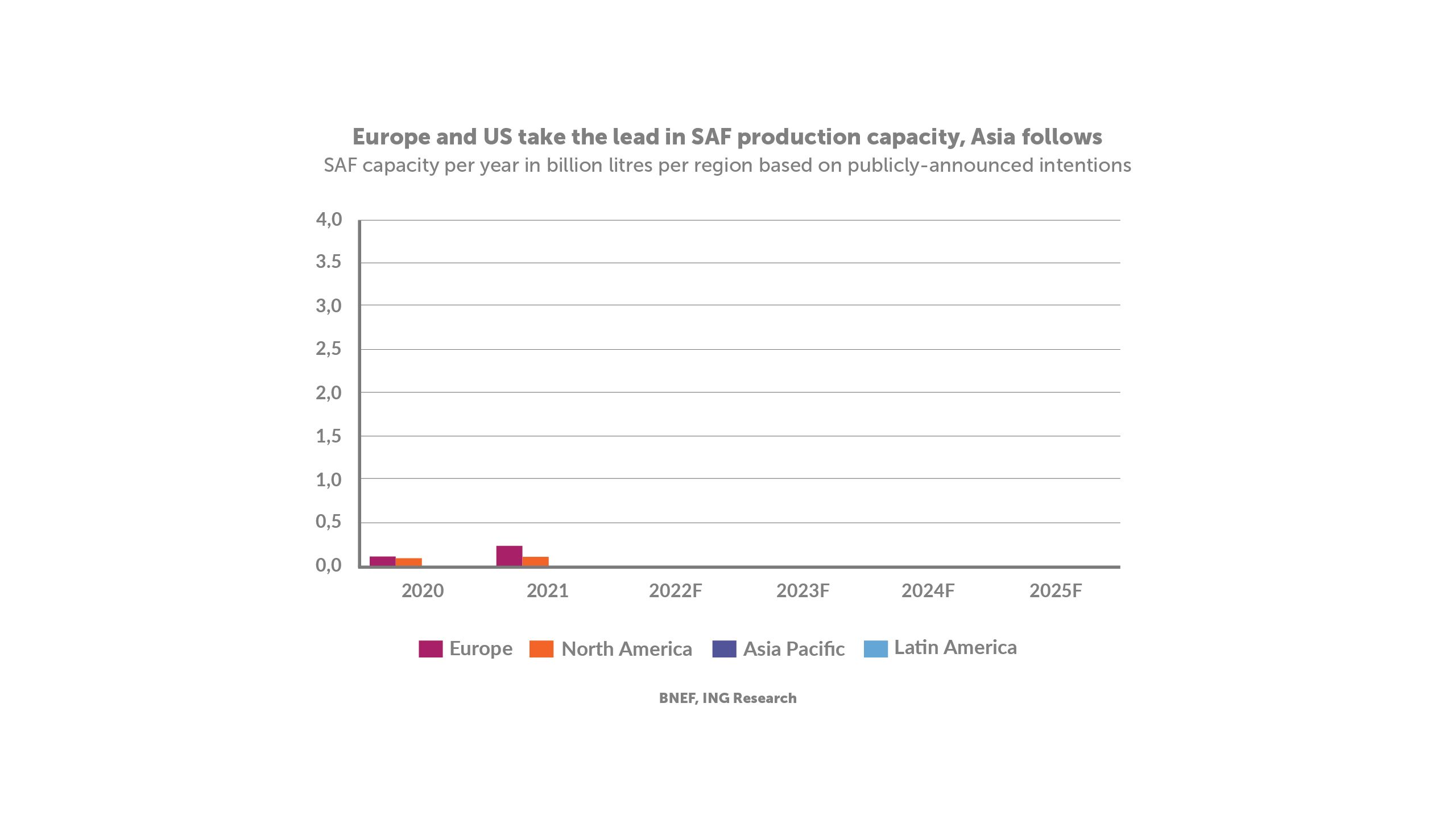

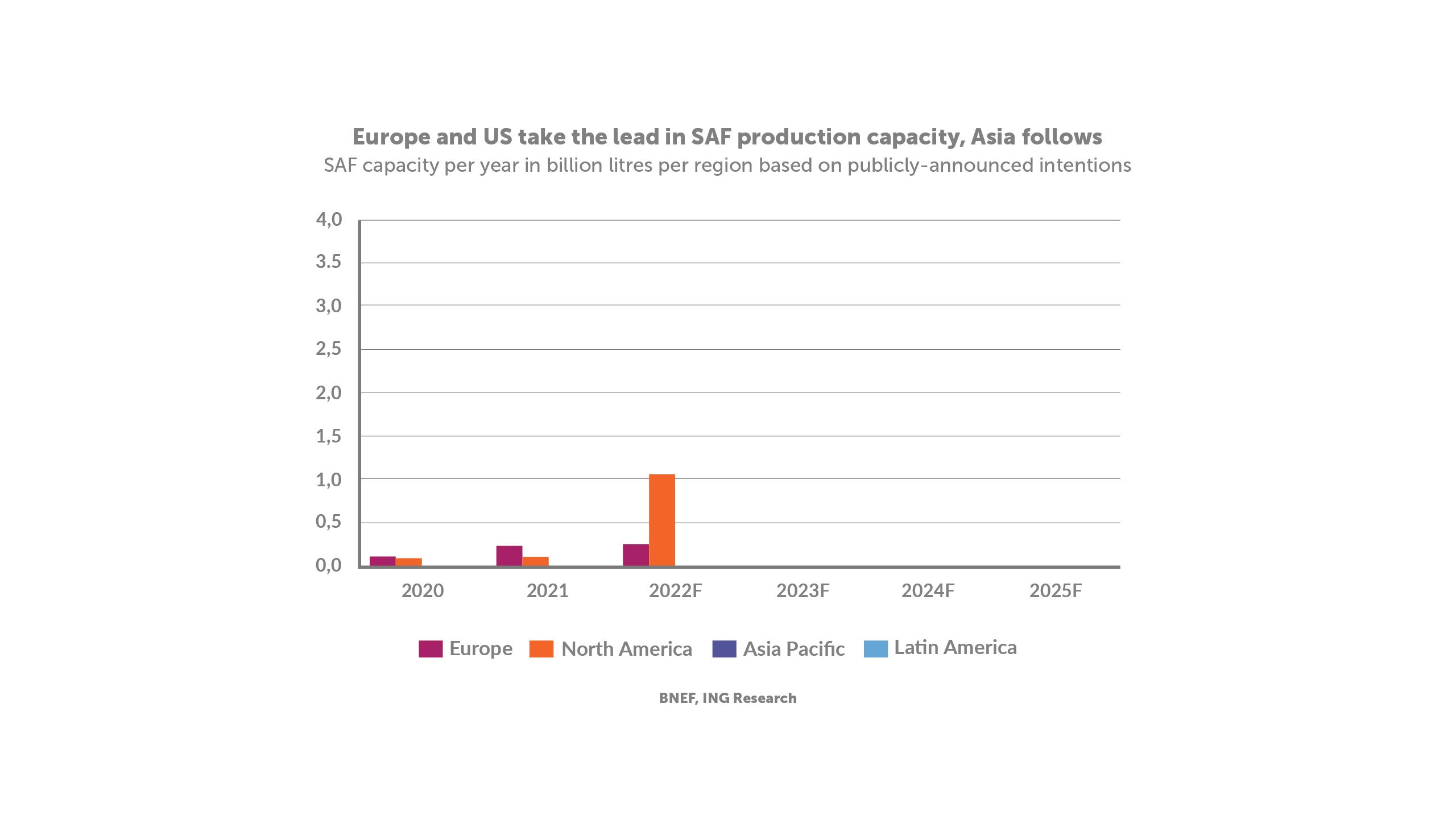

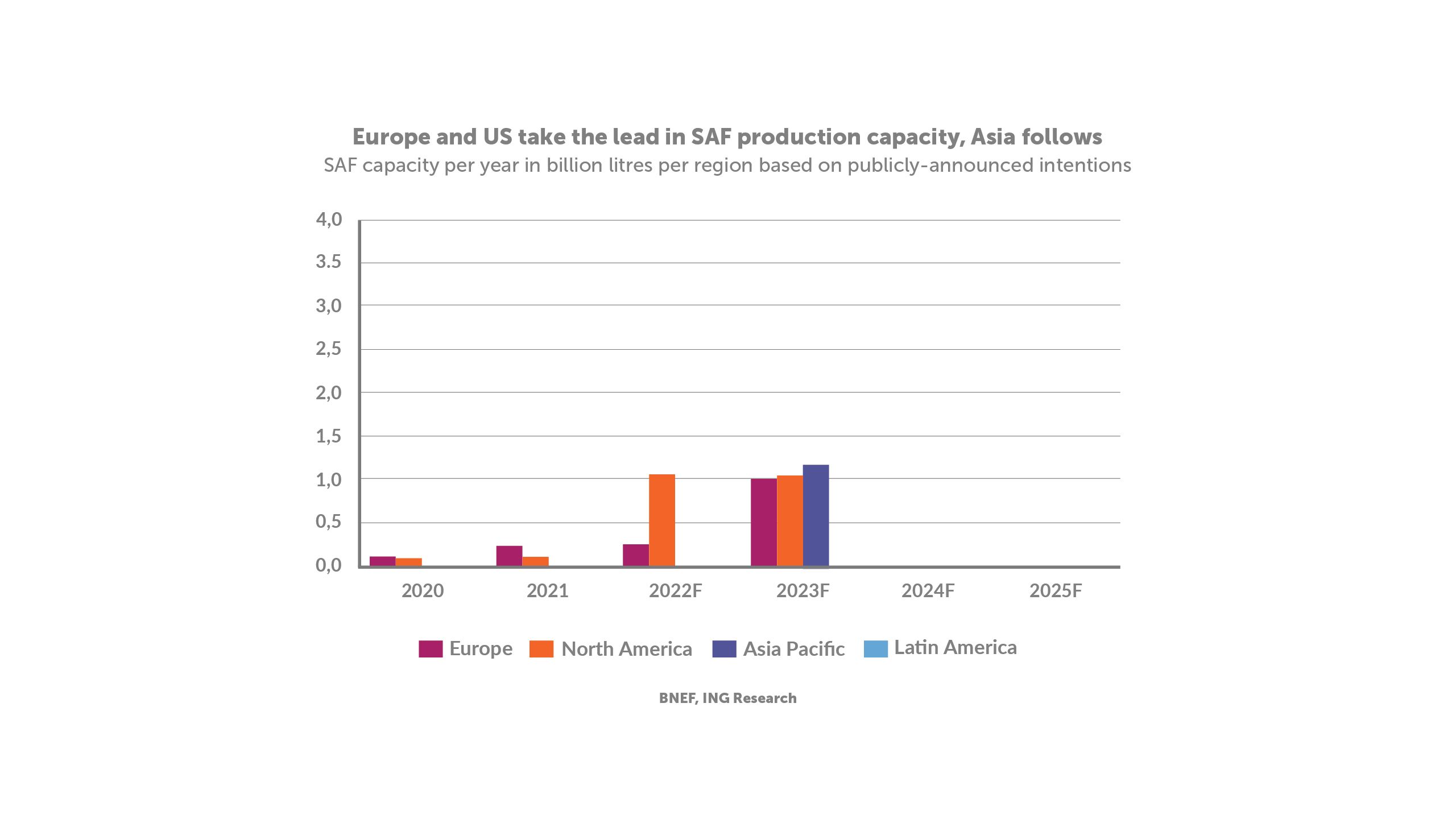

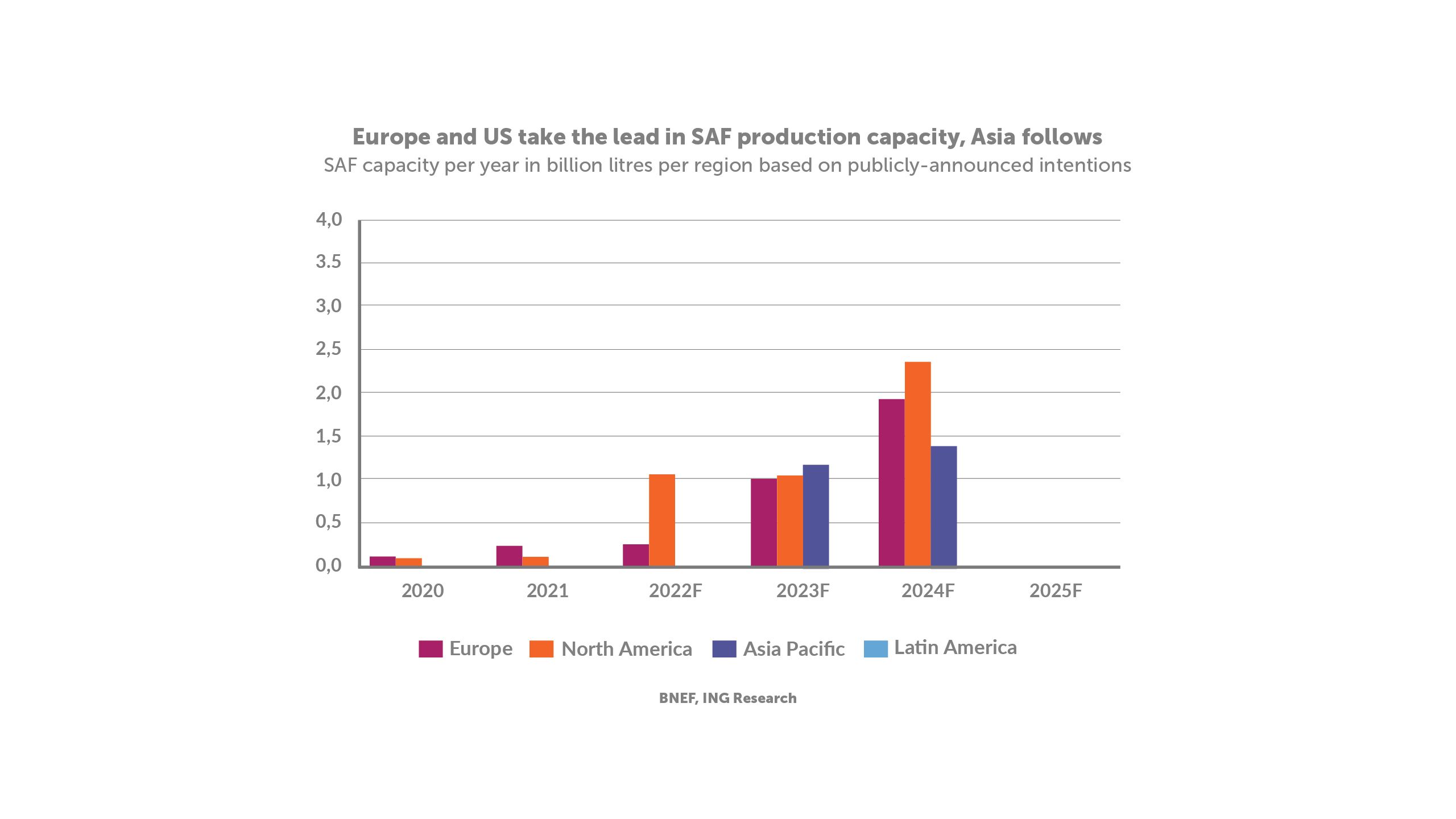

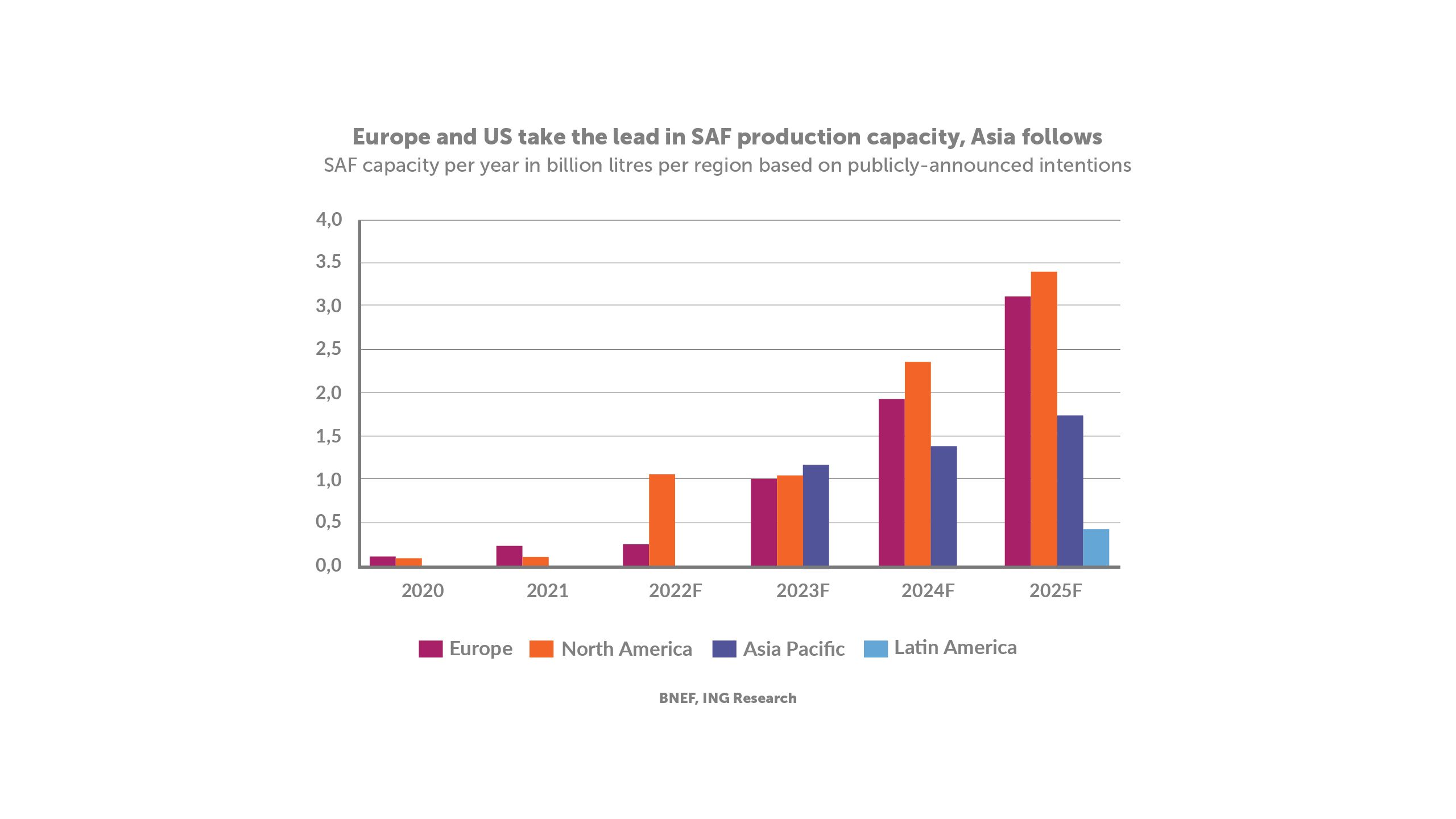

Many countries have jumped onboard and are making strides to help stimulate production. North America is taking the lead, with Europe, particularly Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and the UK, not far behind.

In 2022, the US government announced tax credits along with a grant programme to help stimulate the supply of SAF. The target is to produce 3 billion gallons a year by 2030 and 35 billion gallons a year by 2050.

In the EU, the European Council announced the ReFuelEU aviation initiative in September 2023 with the aim of kickstarting the large-scale production of SAF. A key condition of this is that fuel suppliers ramp up their supply of SAF from 2% in 2025 to 6% in 2030 and 70% in 2050.

In the UK, the Jet Zero strategy set a target of ensuring at least 10% of jet fuel is SAF by 2030. To help meet this target, the Advanced Fuels Fund with its £165 million in grant funding was announced together with a commitment to have at least five SAF plants under construction by 2025. More recently, in September 2023, the government announced a revenue certainty mechanism to help boost investment and support SAF production.

According to ING, the Asian-Pacific region is falling behind other regions in terms of SAF production capacity, despite its rapid expansion in air travel over the past decade. In China, the production of SAF is only just getting started and part of the reason it’s lagging behind, according to a report published by the Institute of Energy at Peking University, is predominantly down to there being no top-level policies to incentivise investment in production and get the industry moving.

On track to meet ambitious targets?

With the enormity of the task and the fact that there is currently only a handful of commercial SAF plants, will production scale sufficiently in the coming years to achieve the 2030 targets, let alone net-zero targets in 2050? IATA seems to think so. It states that more than 130 relevant renewable fuel projects have been announced publicly by more than 85 producers across 30 countries.

As well as start-ups hoping to scale up, established producers are also expanding production. For instance, Neste is constructing SAF production capacity in Singapore and the Netherlands, to add to its existing production facility in Finland. In the UK, LanzaTech is developing a production plant in Port Talbot, South Wales, that will use waste emissions from the Tata steel factory, and Fulcrum BioEnergy is developing a refinery at Stanlow, Cheshire, that will supply SAF to Manchester Airport using non-recyclable residual wastes as feedstock.

In terms of synthetic PtL fuel, Airbus has already partnered with the SAF+ Consortium, a Canada-based organisation that is developing a PtL SAF plant in Montreal with the aim of targeting wide-scale PtL production. Meanwhile, in Europe, according to ING, several low-volume production facilities for synthetic SAFs (including in the Netherlands and Sweden) are planned to come online between 2025 and 2030.

The race is very much on. To deliver SAF at scale and meet production targets will require consistent and supportive government policies across countries. While some regions are in the lead, decarbonising aviation is a global challenge that will require international collaboration and partnerships.

You're reading a brand new digital publication from the team at Professional Engineering, made exclusively for IMechE members and available on all devices. We'd love your feedback: let us know what you think at profeng@thinkpublishing.co.uk