Electrification gets heavy

Some of the biggest polluters on the roads are going green thanks to increasing accessibility of battery technology and some ingenious engineering.

For many years, full electrification was mostly reserved for passenger cars only. Some bus services got a hybrid upgrade, and there was the occasional hydrogen fuel-cell trial, but heavy commercial vehicles were largely seen as impractical targets for battery-based powertrains.

That has all started to change. With net-zero targets rapidly approaching – the UK will phase out new non-zero-emission heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) weighing less than 26 tonnes from 2035, and all new HGVs will be zero-emission by 2040 – and low-carbon technology getting more advanced each year, electrification of the heaviest vehicles no longer seems out of reach.

Tesla in the US might grab most of the headlines, but 2023 has seen a flurry of UK projects dedicated to preventing emissions from some of the biggest polluters on the roads – Bramble Energy’s printed circuit board fuel cell could power a hydrogen double-decker bus, for example, potentially preventing 6 million tonnes of CO2 from being emitted, while EDF Renewables and the Oxford Bus Company took steps to enable a fleet of electric buses for the city.

Elsewhere, Yorkshire company Technical Services is helping firms electrify everything from road sweepers to buses, and Glasgow’s Hydrogen Vehicle Systems and Essex firm Tevva are racing to get the first hydrogen-electric HGV into commercial operation.

With so many projects under way, electrification of heavy vehicles is clearly en route – but how quickly will we reach the destination?

Engineering extremes

Unlike cars, lorries need to be available 24/7, says David Bond, head of platform engineering at Tevva – hence the slower electrification. “It’s a workhorse that the logistics company buys, and they expect to maximise that. They're not sitting on somebody's drive… there aren't the same opportunities to charge,” he says.

“The other thing is they've got to carry very large payloads, so the daily energy requirement is much larger.”

The trade-off between range and payload brings some major engineering challenges, including picking the right size battery. This is compounded by the varied usage between customers.

“At one extreme, you could be a bakery in central London, and you might have only a 400kg or 500kg payload, and you might only do 10 or 20 miles a day,” says Bond, who previously spent two decades at Jaguar Land Rover, including as engineering manager on the Jaguar I-Pace.

“At the other extreme, you might be a company in the North of England that manufactures bricks, and you're looking to take 10-20 tonnes of bricks over the Pennines every day.”

That extreme might be out of reach for now, but Tevva hopes to meet many other large payload applications with its purely electric trucks, built in Tilbury. Its 7.5-tonne electric truck can carry a body and payload of almost 3 tonnes, which Bond describes as “the heavier payloads of last-mile delivery,” with a range of up to 180km.

The falling price and increasing energy density of commercially available battery cells has helped make Tevva’s vision possible, Bond says, as well as gradually improving infrastructure.

The firm has boosted the efficiency of its regenerative braking technology thanks to an electronic braking system (EBS) from ZF, which was adapted by Tevva engineers to integrate traction control with the braking and regen. The blend of friction braking with the e-motor reduces wear and tear, says the company, while recuperating up to four times more energy than a traditional air-brake system.

A dual-motor system, developed with Advanced Electric Machines in the North East of England, also reportedly allows increased efficiency and redundancy, while a future hydrogen variant could boost the range to 435km.

Fighting physics

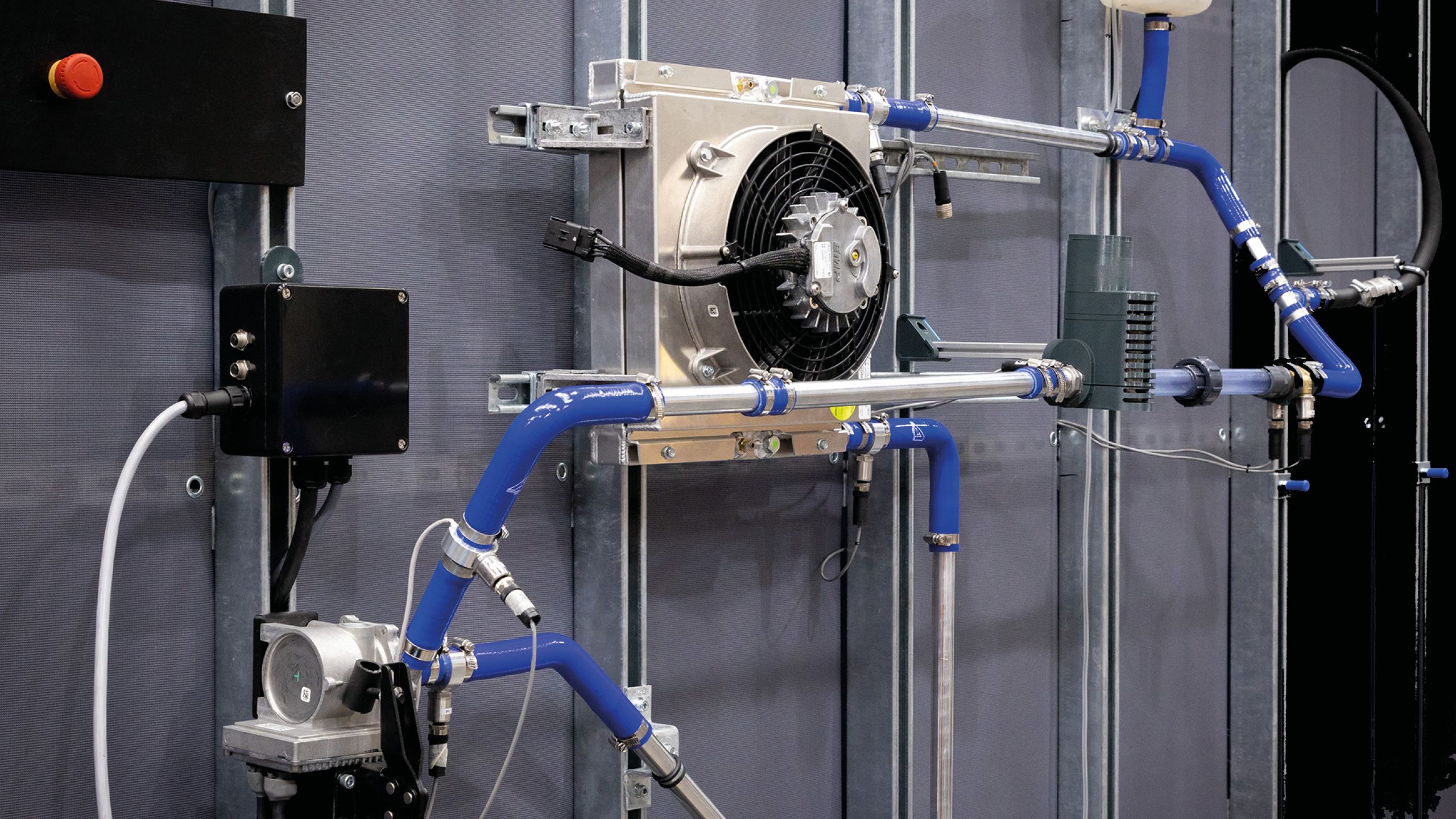

Brand-new designs are not the only way to go electric, however. Technical Services has provided its thermal management expertise for electric conversions including hybrid buses and construction equipment, and is working on a hydrogen fuel-cell range extender for use in emergency vehicles such as ambulances and fire engines.

High voltage thermal management system

High voltage thermal management system

Space constraints and heat management are some of the biggest challenges in conversions, says Andrew McMahon, sales and engineering director. “The physics are a little bit against us, in the sense that we have the same surface area, quite large amounts of heat to reject,” he says. “We ultimately need to do that through a clever cooling system, using all the available space that's there for us.”

These hurdles are made even more difficult by a narrower temperature tolerance – batteries typically want to be 25-28ºC, up to 35-40ºC, says McMahon, and higher temperatures mean reduced performance and additional ageing. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, however, owing to different operating conditions in different countries.

Ramping up

There is a lot of demand for conversion work as petrol and diesel are phased out, says McMahon. “It’s an unbelievably busy time at the moment, which we're very grateful for,” he says. “The early adopters were the smaller vehicles that were battery-electric, and a lot of lessons were learnt with battery-electric vehicles and the various additional cooling that was required.”

He adds: “Battery-electric alone doesn't really work on a commercial vehicle platform when it's predominantly running much longer hours, much longer distances, carrying much heavier payloads. So the introduction of fuel cells, or incredibly fast charging, or swapping out batteries, come into play in order to enable those.”

Looking at the wider market, Tevva’s Bond says most logistics companies will be using EV vans within two to three years. He predicts 7.5-tonne rigid trucks with range below 200 miles (322km) – more with hydrogen – to take over in three to five years, while the articulated lorries with the heaviest loads and short wheelbase will take until 2030.

That is all far from easy, however. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders has said the zero-emission HGV market is “shackled by absence of infrastructure and a lack of plan”. It has called for a government strategy to drive uptake, including competitive purchase incentives and a national plan for installing depot infrastructure.