FOSSIL FUEL POWER STATIONS COULD ACCELERATE NET ZERO

HERE'S HOW

A new generation of geothermal power systems could access extreme temperatures deep underground – and disused fossil fuel power stations could provide an ideal opportunity to turn that heat into electricity. We spoke to developer Quaise Energy about how it plans to transform the race to net zero.

It sounds like a fantasy – reusing coal power stations to provide electricity without the carbon emissions. But it could become reality in the next five years, thanks to a new approach to geothermal power.

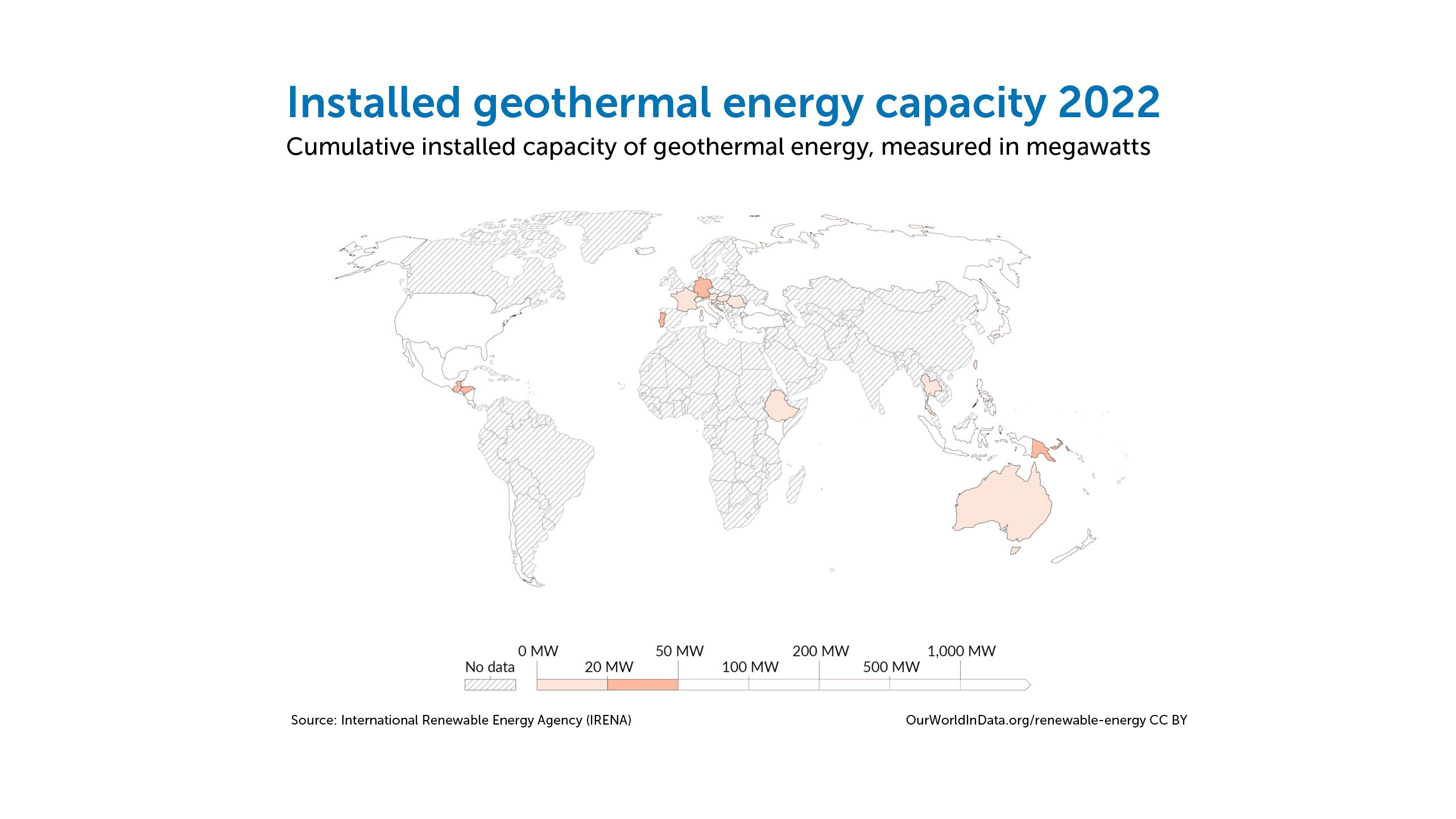

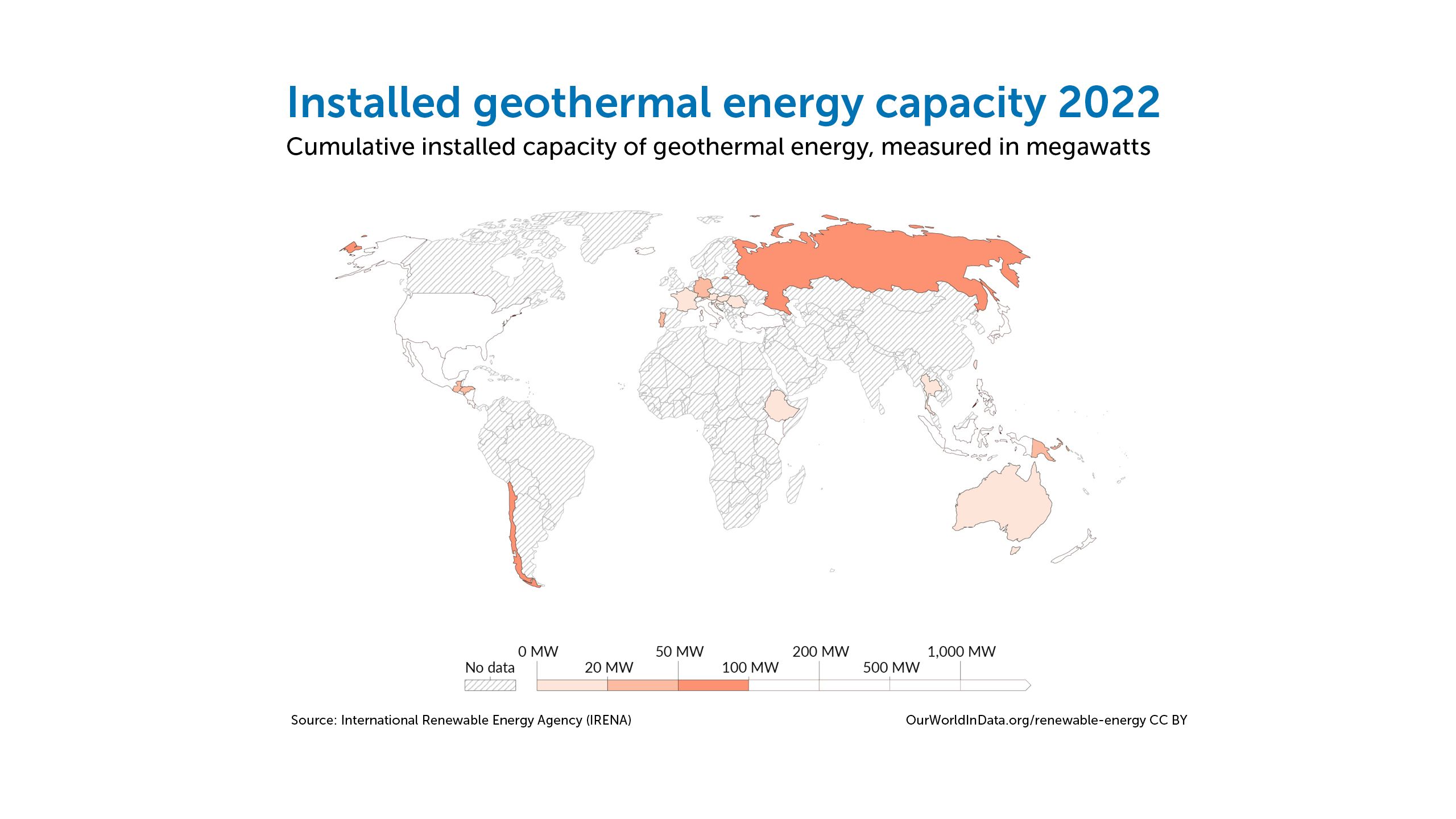

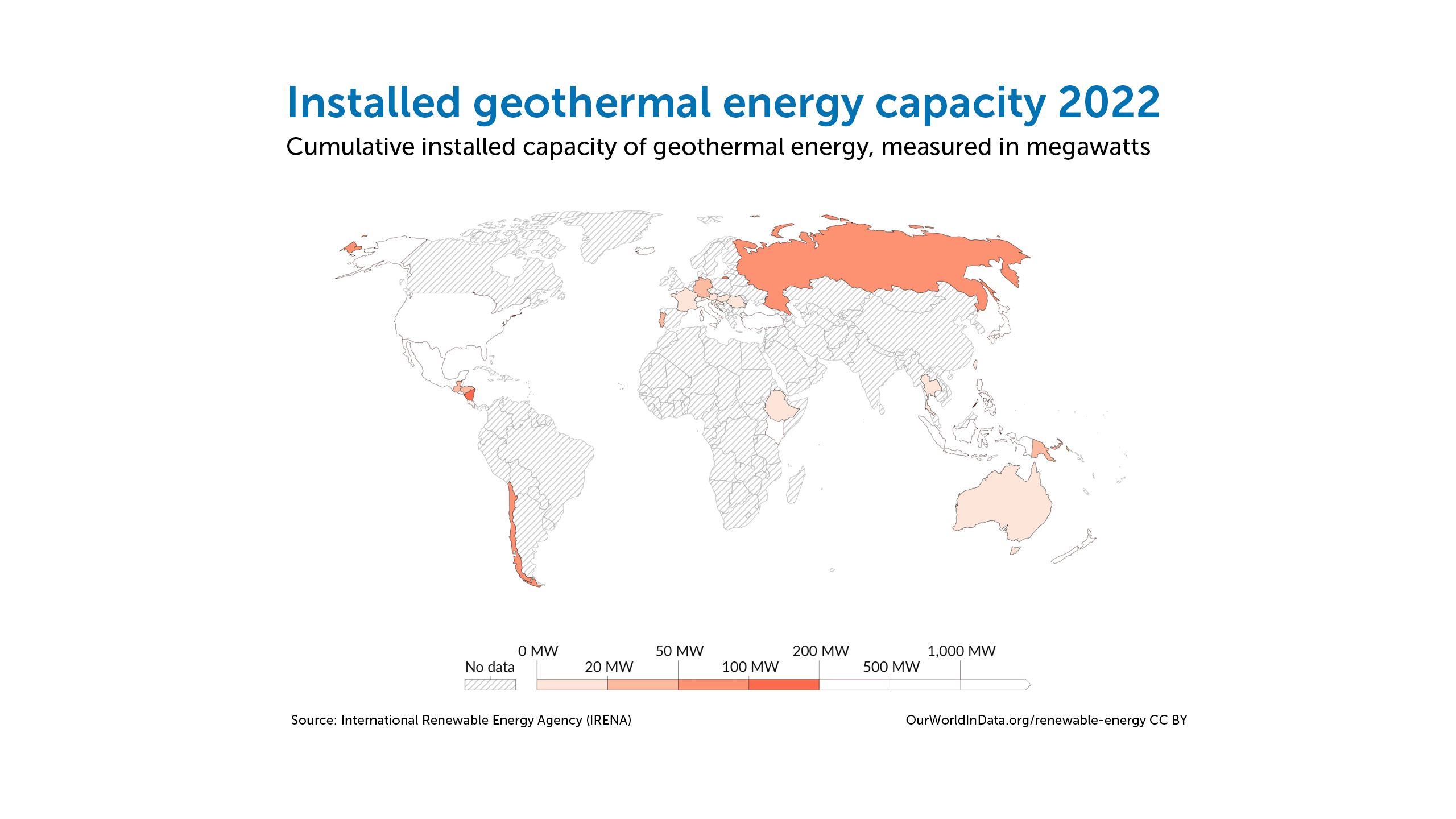

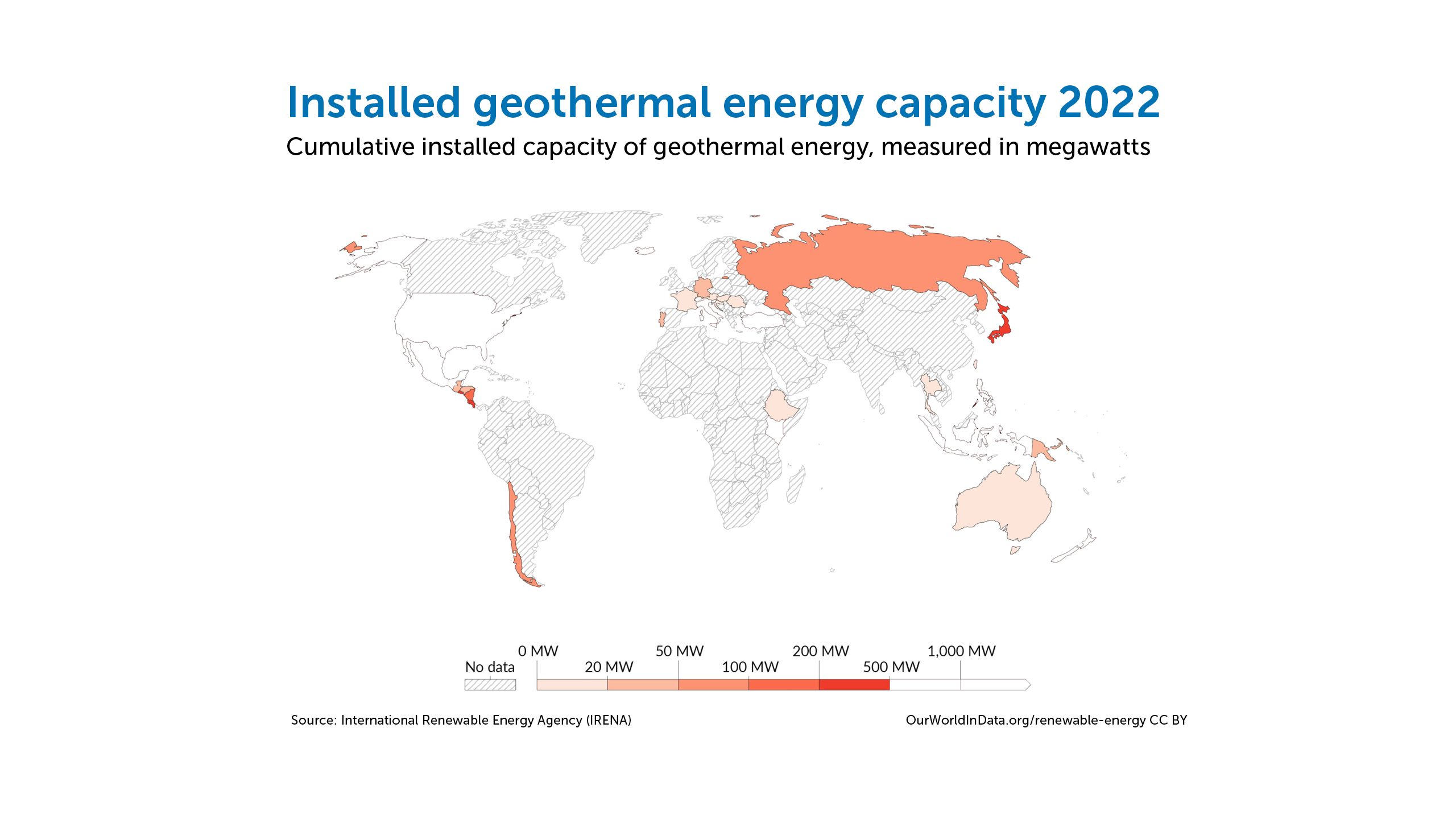

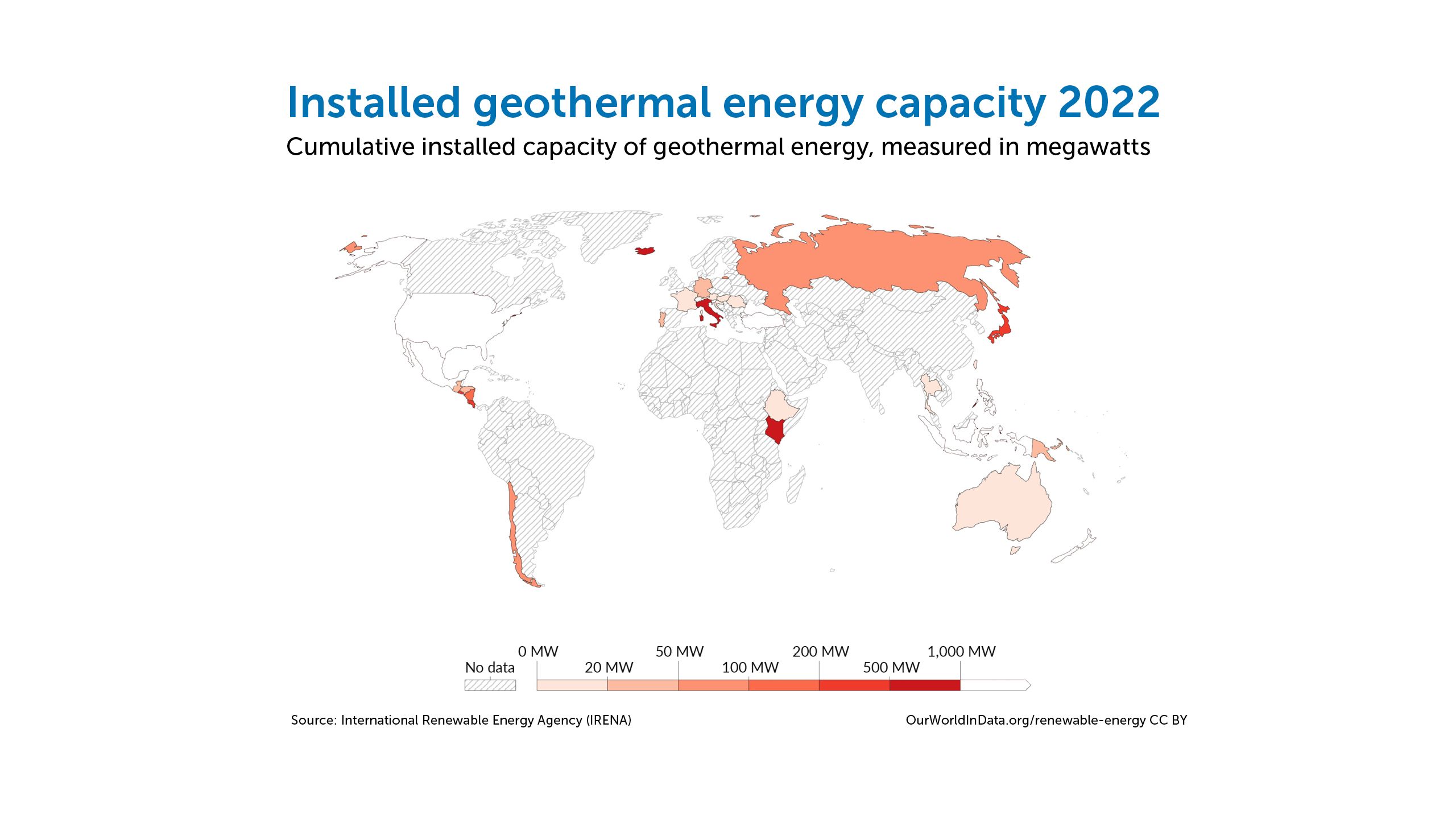

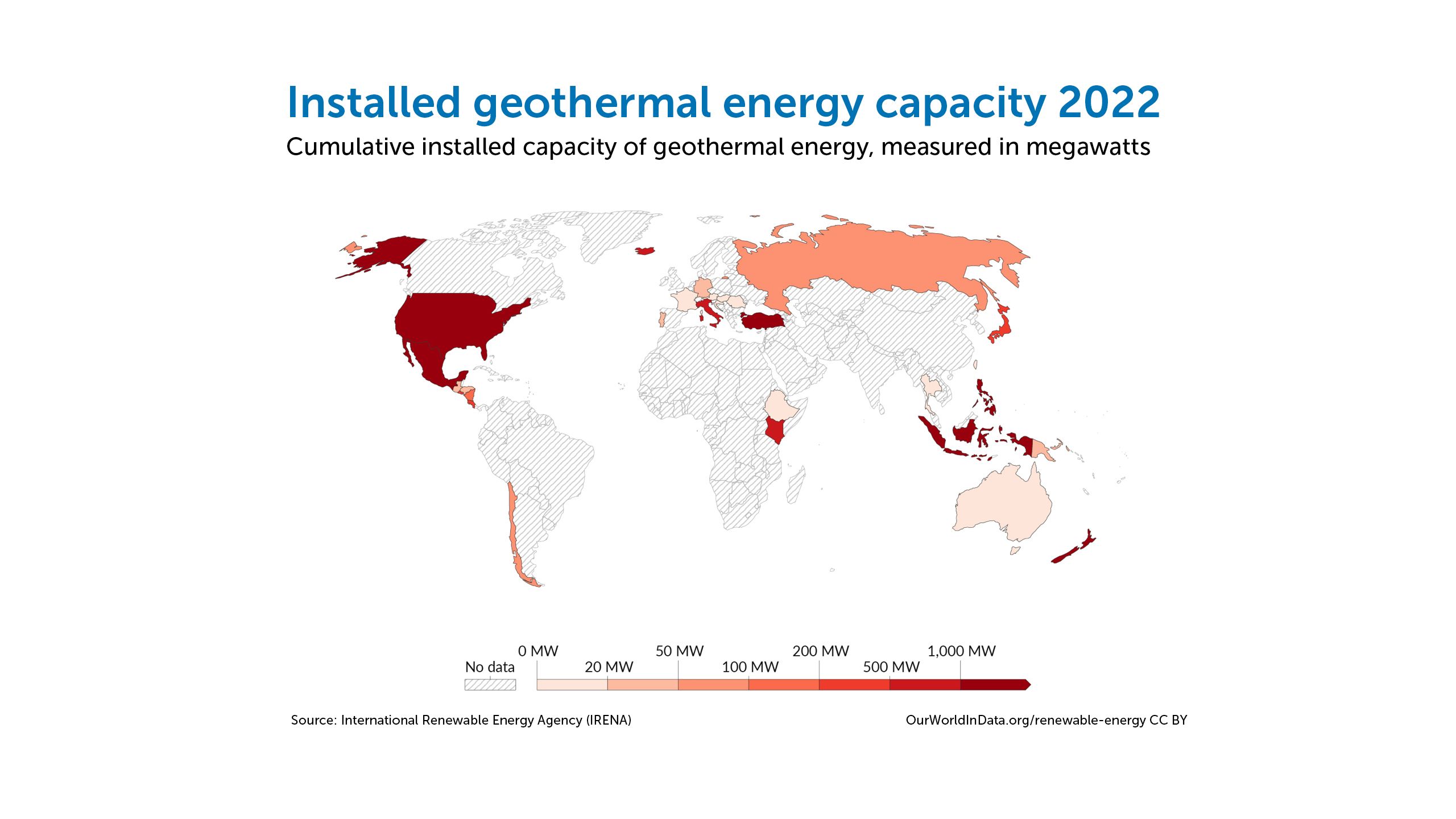

Conventional geothermal systems only penetrate to a maximum of 3km, where they access hot, permeable rocks and fluid that transports heat to the surface. These requirements mean their installation is typically limited to areas with volcanoes or hot springs.

New Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) could go much deeper, accessing impermeable rocks 20km underground. At those depths, geothermal energy could be tapped around the world, with temperatures of 300-500ºC – which, used to generate steam from injected water, could power turbines in defunct brownfield power stations, providing easily exportable renewable electricity.

That is the vision of Massachusetts firm Quaise Energy, one of several companies pursuing EGS as a solution to net zero. We spoke to co-founder Matt Houde about how it plans to use a drilling technique based on nuclear fusion research to “unlock the true power of clean geothermal energy”, taking lab-tested techniques out into the real world.

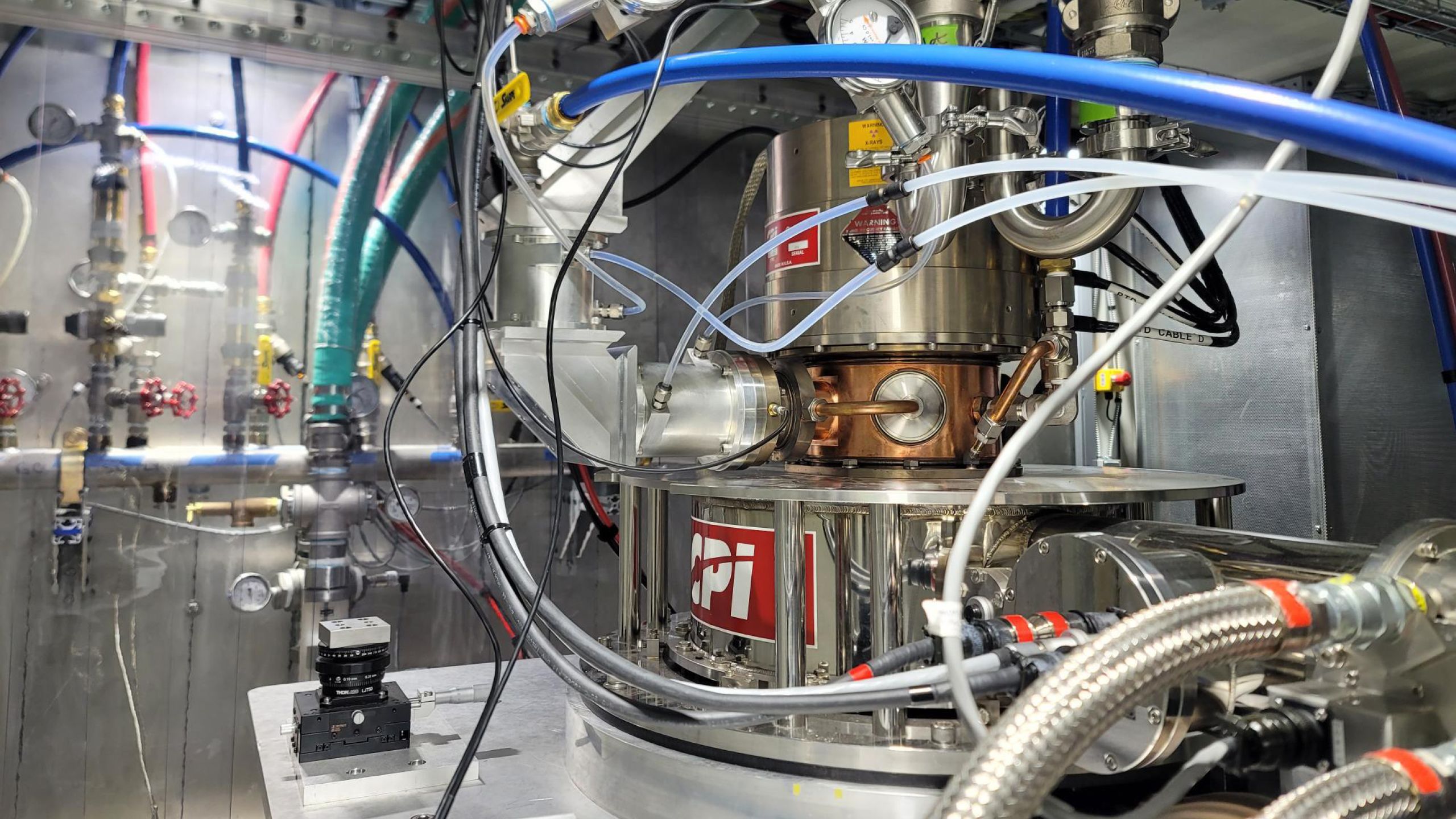

Utah Forge is testing key technologies for Enhanced Geothermal Systems (Credit: Eric Larson, Flash Point SLC)

Drilling down

Getting down to the granite ‘basement’ rock 20km below the surface will be no easy task. The intense heat and the harder, impermeable rocks, means conventional rotary drilling would quickly become impractical.

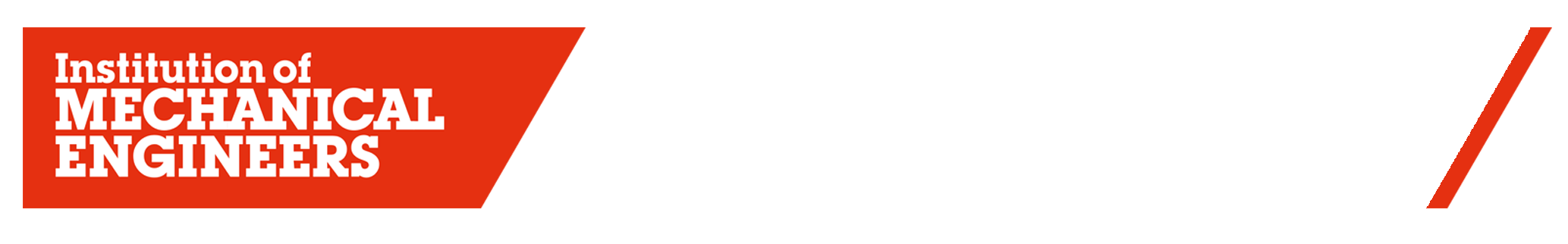

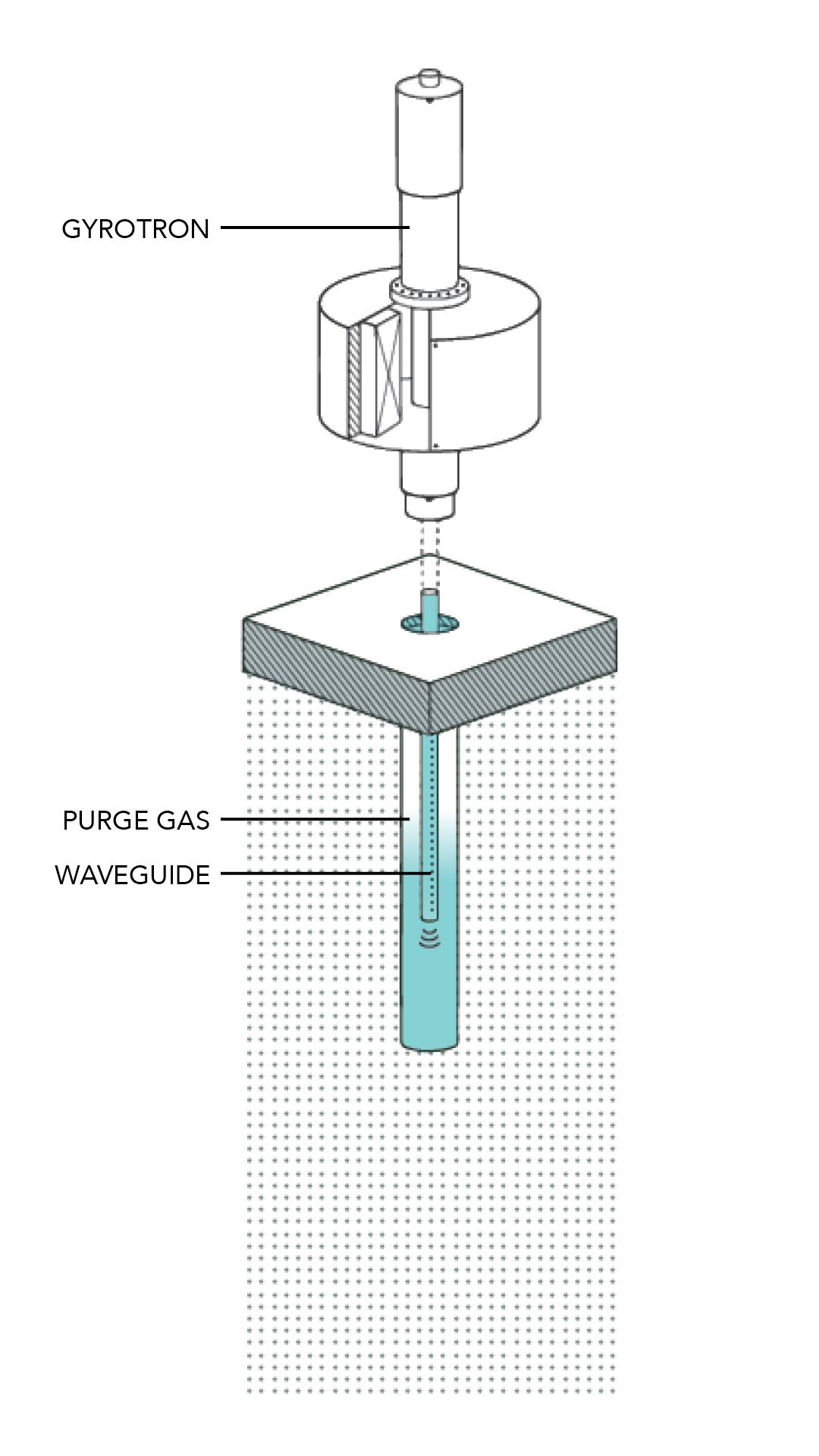

Instead, Quaise plans to use ‘millimetre wave drilling’, directing concentrated beams of microwave energy to melt and even vapourise the rock.

Millimetre wave drilling requires two things, Houde said. “It requires a lot of microwave energy, and it requires a means to transmit that energy very efficiently over long distances, such that you can drill these deep boreholes,” he said. “The millimetre wave spectrum provides the ‘Goldilocks area’ of satisfying both of those objectives.”

The 30-300 gigahertz microwaves will be provided by a device called a gyrotron, originally developed for nuclear fusion research. Electricity is sent to a large vacuum tube, Houde explained, generating a high-voltage electron beam. A strong magnetic field is applied, and its interaction with the electron beam produces the microwave energy.

A one-inch diameter, 100-inch deep hole drilled in the Quaise lab in Houston (Credit: Quaise Energy)

A one-inch diameter, 100-inch deep hole drilled in the Quaise lab in Houston (Credit: Quaise Energy)

Capable of generating over 1MW of microwave power, the gyrotron will sit at the surface, eliminating the risk of equipment failure in the extreme underground conditions. Current devices can reach 50% efficiency, and Quaise hopes to increase that further to improve drilling efficiency and reduce costs.

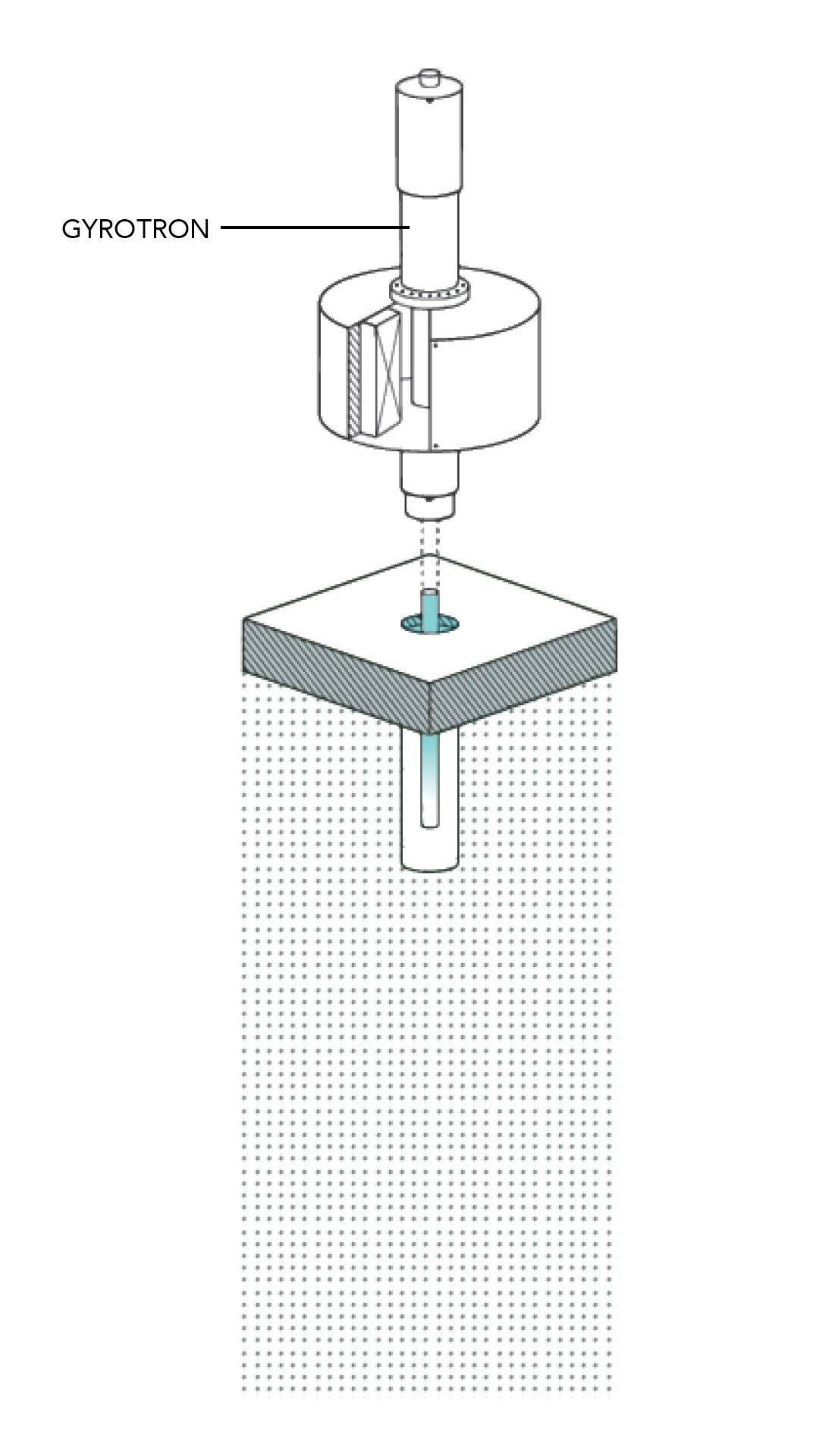

A surface transmission line will deliver the microwaves from the gyrotron to the downhole ‘waveguide’ section, directing them towards the deep, high-temperature geothermal resources.

Cutting edge

Drilling the hole through rock could involve a combination of techniques, including ablation, melting, and even vaporisation at 3,000ºC. “Literally the only real area of research for rock vaporisation as a common phenomenon is the ablation of meteors and meteorites entering the atmosphere,” Houde said. “It is not a common occurrence by any means.”

Quaise is focused on finding the optimum way to drill the 20-25cm diameter boreholes, whether that is a pulsed or a constant microwave beam.

“Generally, the only reason to not solely rely on continuous generation… is to ensure we're properly managing temperature down-hole, that we are suppressing and mitigating any form of plasma that may form at the bottom of the hole as this rock ionises,” said Houde.

The main environmental concern will be removing and storing the very fine ash produced by vaporisation, he added.

Power balance

The drilling rig will likely require 3-5MW of input power to provide 1MW of output power and inject ‘purge gas’ to remove the waste rock.

That high-power work should pay dividends, however – by accessing very high temperatures of about 400ºC, a geothermal installation could produce 30-50MW of power at the wellhead. Three holes – one to inject cold water and two to return super-hot fluid – could pay back the energy input within 50 days or so.

Reusing fossil fuel infrastructure to generate electricity will be a “win-win situation” for everyone involved, Houde claimed. “The power plant operator is able to keep their plants operating, workers are able to retain the jobs without burning of coal or any sort of fossil fuel, whereas we have an ideal site,” he said, including existing permits, interconnections and water access.

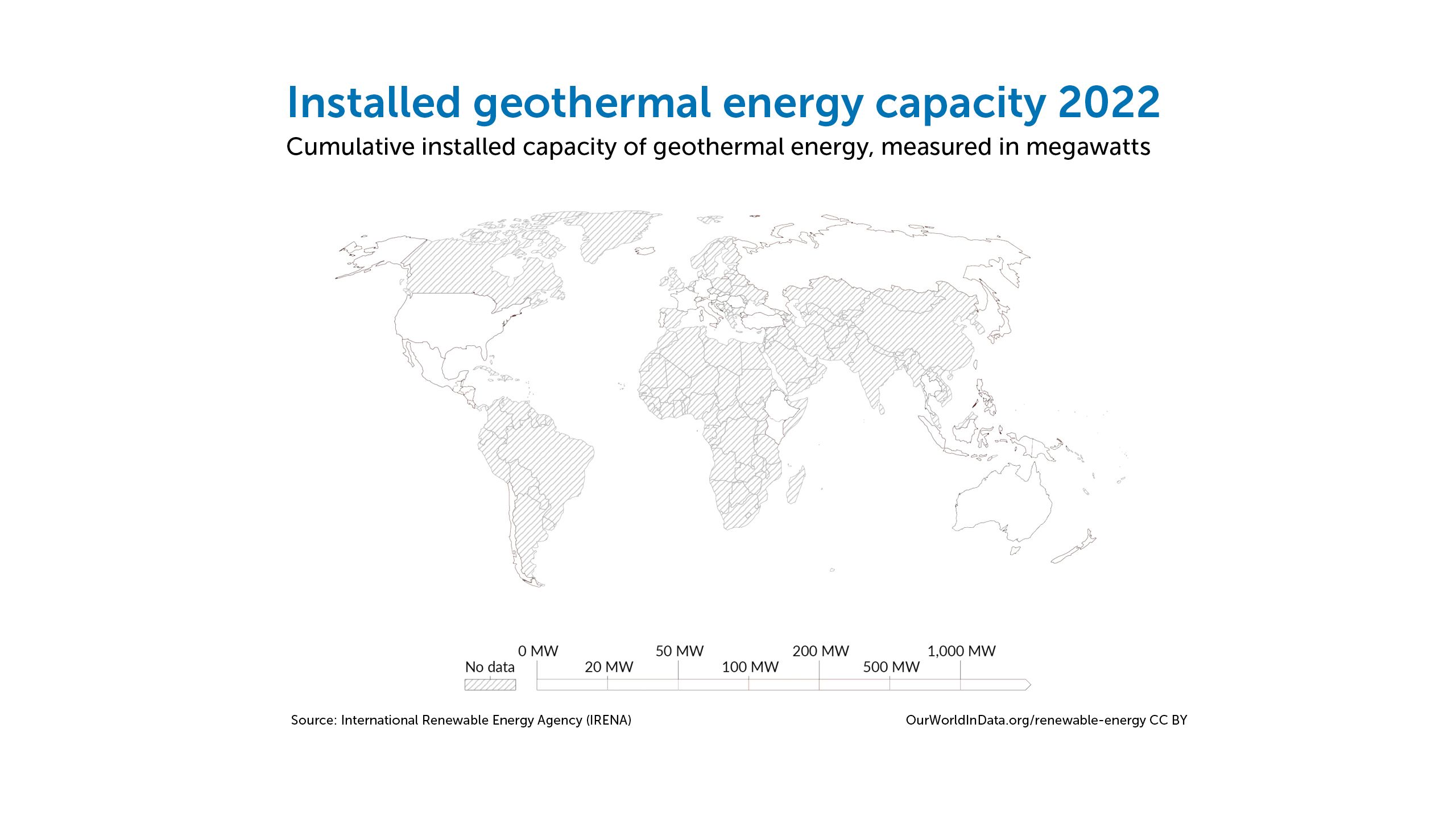

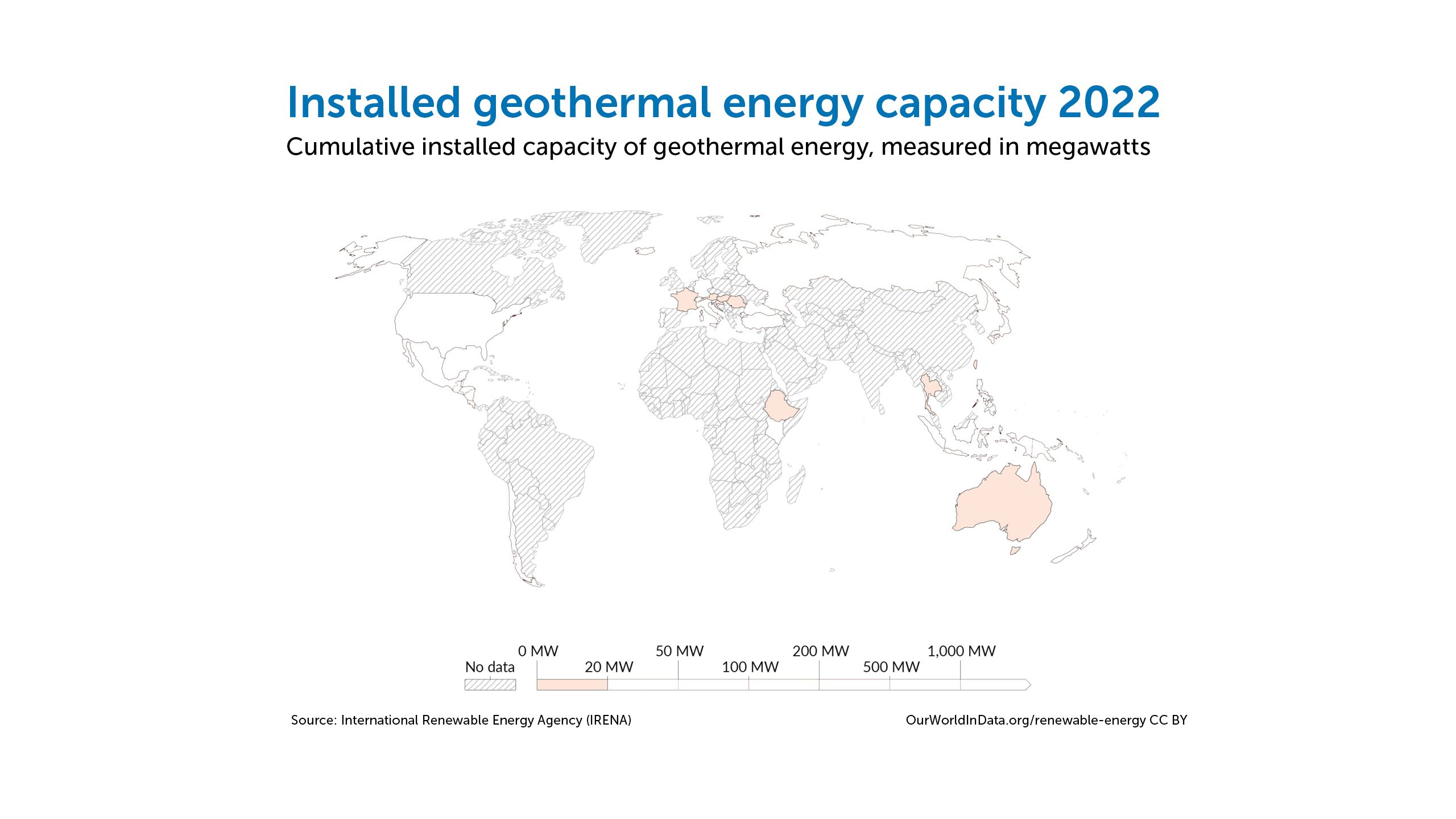

By drilling deeper than ever before, suitable locations could be found around the world, greatly expanding the current global capacity of just over 15GW and accelerating the energy transition.

“Very big scale is what we want to aim for,” said Houde. “That's what we need for geothermal to really play at the same level as what wind and solar do today.”

That could include the UK – according to the Association for Renewable Energy & Clean Technology, independent analysis showed that the UK’s deep geothermal potential equates to 20% of the country’s electricity consumption, and 100GW of heat production.

The gyrotron on the surface provides the high-energy microwaves

The gyrotron on the surface provides the high-energy microwaves

The waveguide directs microwaves down the borehole

The waveguide directs microwaves down the borehole

Purge gas removes waste material from the hole

Purge gas removes waste material from the hole

The Quaise Energy gyrotron (Credit: Quaise Energy)

Seismic challenge

While maturing the drilling technology is a major aim, it is “only half the equation” for Quaise. Techniques similar to hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking in the oil and gas industry, will be needed to create geothermal reservoirs that efficiently extract heat.

Given the concerns and controversy around fracking-induced seismic activity, could the issue threaten the environmental credentials of EGS?

Matt Houde (left) with the rest of the Quaise Energy leadership team (Credit: Engine Ventures)

Matt Houde (left) with the rest of the Quaise Energy leadership team (Credit: Engine Ventures)

“Induced seismicity is something we constantly want to be monitoring and mitigating,” Houde said. “The geothermal industry has actually – despite some initial incidents that were quite concerning – had some big successes over the past couple of years, with the [Utah] Forge project and other companies like Fervo Energy, in terms of minimising – not outright eliminating – that induced seismicity concern through careful monitoring and mitigation.”

Aiming to de-risk tools and technologies for EGS, the Forge project uses dedicated seismic monitoring wells fitted with accelerometers, acoustic sensors and seismometers to detect activity.

A nine-hour ‘stimulation’ test, in which water was injected into and through an EGS reservoir in hot dry granite, did induce seismic movement – but nothing above 1.9 on the Richter scale.

“You won't feel it at all, even if you're standing there,” said Forge principal investigator Dr Joseph Moore. “If you go then to 3, you will feel it. Activities have to stop.” This is handled by a traffic light-style system, which pauses or stops operations when required.

Dr Moore, who has worked in geothermal power since the mid-1970s and managed the Forge project for 10 years, said EGS fracking will be different to fossil fuel fracking, which uses permanent injection sites. There, tens of millions of gallons of water are injected into the ground, which can eventually “fill up like a sponge”. That lubricates underwater fractures, which can slip and cause earthquakes.

EGS, on the other hand, cycles the water rather than keeping it underground. “The water that we inject into the well to make the system work is continually reinjected,” Dr Moore said. “Ideally we want 100% reinjection. 90% would be great.”

Global opportunity

This year, the focus for Quaise is transitioning the technology out of the lab into the field. The company has new gyrotrons and waveguide transmission lines designed to repeat tests carried out at MIT with greater power, drilling larger diameter holes at much faster rates.

The team aims to use a mobile prototype to dig a 1km hole next year. It is also developing a full-scale millimetre wave drilling rig with Nabors Industries, a manufacturer of rigs for the oil and gas industry. The system’s hybrid approach will use conventional rotary drilling at shallow depths, before switching to millimetre wave to penetrate harder rock below. The first field trials are planned this year, with plans to drill a full-size hole within the next two years.

“We know that this is something that's extremely challenging. There's going to be a host of risks and challenges,” Houde said. “But we know that the reward for achieving success here is clean, firm power. It's providing a technology, a new primary source of energy that can really help accelerate the energy transition.”

The Quaise website makes the bold claim that “it is the only renewable solution with the potential to get us to net zero by 2050” – something that many engineers working in wind and solar energy would likely disagree with.

“There are ways to decarbonise the grid and provide power 24/7 through only those sources, but I think there are serious trade-offs,” said Houde. These include overspending to counter intermittency, huge costs for storage, and significant land use, he claimed. Quaise hopes EGS could be cheaper, with less of a footprint and without the geopolitical challenges of nuclear energy.

Perhaps the most likely future scenario is countries using EGS to complement intermittent sources, as suggested by a study by Fervo Energy and Princeton University. By operating plants flexibly, the team found that the value of the geothermal energy increased dramatically.

Quaise aims to repower the first former fossil fuel plant with geothermal steam by 2028. Challenges remain to be solved – but achieving net zero means we need to dig deep.

A drilling rig at Utah Forge (Credit: Eric Larson, Flash Point SLC)

A drilling rig at Utah Forge (Credit: Eric Larson, Flash Point SLC)

Don’t miss a full interview with Dr Joseph Moore from Utah Forge – subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

You're reading a brand new digital publication from the team at Professional Engineering, made exclusively for IMechE members and available on all devices. We'd love your feedback: let us know what you think at profeng@thinkpublishing.co.uk